SCU’s Anomalous Aerospace Phenomena Conference (AAPC) 2023 – Day 1

Every podcast, tweet, article … every everything UFO or UAP has, of course, been agog with the Grusch bomb since that fateful day last month. One is left wondering: Will this be one of those “do you remember where you were when Kennedy was shot” moments? (The reference is particularly unsettling, of course, since the recent Schumer legislation, in an act of perhaps unwilful entwinement of real-life intrigue with the sensationalist fluff of conspiracist fantasy-mongering, bases itself on that surrounding efforts to declassify and release documents related to the Kennedy Assassination.) The fallout is left hanging around like a White Noise-style miasma following – in this case – the hapless among us who wish to move on to the more fundamental question of evidence. It is not just a fundamental question, without an examination of which we make no progress in the empirical, factual study of UAP qua object of science (a fraught question, to be sure, and one worthy of careful epistemic diagnostics); it is also a rather basic – no elementary – question.

I will repeat myself: Since no independently verifiable

material evidence has been supplied to the general public, which can

possibly form the basis for a sound, reasonably informed judgment regarding the

factual status of Grusch’s allegations, or which can provide the foundations

for an independent assessment as to whether those with supposed “first-hand”

knowledge (allegedly of crashed craft, anomalous material fragments, or

nonhuman “biologics” associated with any of this) have come to their own

beliefs on a sound basis in fact (just what exactly is it these unnamed

persons with special access have seen, or think they have seen, and are their

claims reasonably secure?) … without any of this, we on the outside of

special government access must remain in epistemic limbo. The only

reasonable position to maintain here is – let’s see the evidence to

substantiate the claims.

I am a bit less inclined than my interlocutor Bryan Sentes is to slide into the skepticism of critical contextualization, which attempts to reduce the current Grusch affair to yet another iteration of some ongoing reproduction of the mythological UFO – “the myth of things seen in the sky” (which by now has become a well-engrained trope on this more skeptical side of the fence). The conversational implication is that the Grusch allegations are dubious because they are more myth than not. I am not inclined towards this position (but one of decided agnosticism) because I distinguish between the mythological UFO and the thing itself, the latter of which stands as an unknown real entering into the sphere of the known (as all “real” phenomena do … and this is the heart of science: even fire was once an unknown). As I have said before, we do not know what to say about these allegations (aside from more speculation both skeptical and believing) just because we do not have access to the relevant evidence. But someone does: namely, the various inspectors general now involved, and who have been involved since at least 2021, as I previously pointed out. (And now apparently there is the first (classified) report of what we should expect will be a number of reports (classified and not) containing the results of their investigations, as I hoped in my previous post on this ongoing affair.)

The mythological UFO (which

surely there is) acts as a kind of cypher or epistemic black box into which

humanity can dump its fantasies (it even brings them into being), to have them

reprocessed and reflected back to us, yielding insights more about the human

than about the unknown that is the object-cause of these mythical (and in some

cases mystical) productions. (This picture of course is complicated by the

phenomenon of the hoax … but let’s not forget that the hoax itself attempts,

in its lying playfulness, to reproduce something unknown that inspires the hoax

itself, and hence the hoax effectively ends up reaffirming the very reality

of the unknown object-cause which it pretends to create.)

The mythological, as with all human productions of meaning,

complicates the being of those phenomena that act as objects-cause of

the mythical productions. I claim that science was precisely that moment that

intersected this mythological world, and countered with a real that acted

against the myths while not entirely refuting them. Thus religion in my

view is an attempt to domesticate some uncanniness, some unknown

phenomenon or phenomena the human being actually encounters (even if only

something emergent from the depths of the human psyche—but what is the psyche?);

as science determines there to be a “natural” phenomenon operating here, the

spell of the myth is broken, and religion is forced to expand or abstract from

its specific and systematic attempt to domesticate that uncanniness – its

theologies or metaphysics is challenged. Religion changes, perhaps adapting to

the new depths provided by the sciences. It is conflictual, to be sure. But on

the side of science, it too must operate with a kind of mythical layer to its

own discoveries and determinations. Science is not free of either ideology or

“myth”.

Here I claim that the myths with which science operates are

those that are determined by the implicit metaphysics with which a community of

scientists operates, especially when offering its treasure: a scientific explanation

of something. In its reductionist tendencies, which posit material

mechanisms as the basis for its phenomena, science becomes mythological and

ideological. This, too, must be neutralized by a counteracting discourse – and

I’ve suggested that this is provided by the standpoint of empiricism, which

seeks a metaphysically neutral stance regarding that metaphysical dichotomy,

for example, between the material v. the spiritual or mental. So, equally,

science, in its own attempts to domesticate the unknown, produces its own

myths. It, too, is an ideological factory as it wrestles with that real

which resists complete or final conceptual, intellectual determination.

The fundamental problem with the UFO phenomenon is simply

that we are confronted with a real unknown, once the procedure of

finding an explanation within the existing boundaries of the sciences is

exhausted. And that’s the rub: there is no general agreement that this point –

the point where we’ve exhausted the set of explanations provided for by existing

science – is ever reached. I have pointed out several times that of course

this is true, because existing science can always be modified to keep up

with anomalies. This is simply an example of the epistemological phenomenon

(which becomes a kind of quagmire) philosophers of science have called

“underdetermination” (about which we’ve opined before in these pages). And this

predicament will never go away. It is simply escaped by theoretical leaps of

faith (a begrudgingly-admitted existential dimension of the sciences),

corroborated by a structure of empirical data and information that can be

coherently and consistently organized by the (new) theory, and if the new

theory can also be systematically linked to that which the new theory

proposes to replace, then we can perhaps forego a radical revolution (although this needn’t be the case – it’s just a good idea

to keep some things we’ve learned in the past as elements or structures,

however modified, within the new theory … something like Bohr’s

principle of correspondence).

We can’t be misled by some wild allegations by some

(seemingly) credible individuals – for which independently verifiable evidence

isn’t immediately forthcoming – to think that all UFO claims are equally

aberrant. Indeed, we might want to see the Grusch bomb as yet another

chapter of the “myth of things seen in the sky” – and maybe it is – but we

can’t let the mythological proportions of “the UFO phenomenon”, which largely

reflects how we human beings have sought to make meaning of these (real!)

“things seen in the sky”, distract us from the more fundamental problem of

the reality of these phenomena as disclosed in the few cases like the one

Cmdr. Fravor recounts to us, and which is by now well known. The literature on

UFOs is replete with such cases. And such literature – correctly described by

Watters et al. (2023) as “grey” – must be seen in proper perspective: as

indications of a kind of phenomenon (a class of variegated phenomena presenting

clear enough physical parameters, amenable to rigorous empirical observations –

hence the development and deployment of observational equipment, as detailed in

the SCU conference, as well as in the Limina conference I organized back

in February) … indications of a class of phenomena that ought to be studied

carefully by some subset of our existing sciences. And studied in such a

way that we’re looking for what appear to be anomalies.

We are on the hunt for anomalies, meaning that we have to

exercise perhaps extra caution that, on the one hand, we’re not finding what we

want to find but that, on the other hand, we’re not excluding what we don’t

want to find, or aren’t supposed to find, either. In other words, we’ve

got to operate in a decidedly liminal space where what is known doesn’t a

priori blind us to the possibility that the unknown (the anomalous) might

require something new from us, conceptually, theoretically, philosophically. We

have to open up to at least four (interrelated) possibilities, all of which,

unfortunately (but necessarily) are already always overdetermined by history,

by myth, by fiction – by a whole realm of existing human meaning-making: new

biology; new intelligence; new technology; new physical principles. Fravor’s

“tic-tac” (which, to repeat, was seen by multiple other witnesses)

speaks to at least three of these four. But we’re hard-pressed to say anything

more specific since we have only witness testimony, some suggestions of radar

data (or other “hard” evidence), and little to no other physical evidence on

which to hang specific hypotheses regarding the how, the who or the

what-exactly (the specific kind of technology he saw – employing the term

‘technology’ here as a placeholder which, indeed, might have to be revisited in

a more critical-philosophical register later on). Fravor’s experiences, and

those of other witnesses like him, constitutes what we might call the suggestive

directional basis for a scientific follow-up – the “grey” literature – that

acts, as in medical science, as an indication as to where, how

and with what suite of instrumentation to look for these kinds of

phenomena. What perhaps is not entirely clear in these discussions is that we

start out in scientific forensics, searching backwards from the

(perhaps scant) evidence at/for the scene of a crime, to the source – the

perpetrator of the crime itself. But in this case, the evidence for the crime,

as it were, is itself suggestive (not “proof”) of means and mechanisms which

our physics and engineering doesn’t fully understand. That adds a level of

complexity to the forensics not typically encountered in this kind of

investigation. But this complexity is why the amateur “investigator” – which

has been the typical person attached to looking into these phenomena, with

wildly varying training and expertise, if at all – isn’t where the empirical

study of these phenomena can end. It’s where it begins, only to at some point

be turned over to those more skilled in the rigors of strict, scientific

observation, data collection and analysis. This is the point at which we transition

from mere forensic investigation to scientific research proper (a distinction

emphasized to me by the architect of GEIPAN’s own system of UAP case resolution

assessment: Michaël Vaillant). Since this proper scientific research program

for UAP hasn’t ever existed in any meaningful sense – quite because of

the stigma attached to the subject, as we all know – no categorical statements

regarding the nature, origins, intentions, physics (or “strangeness”) of any

of these phenomena can really be justified beyond the reasonable conjectures we

can make based on good UFO cases (a statement, I grant, which requires lots of

explanatory follow-up).

More interesting than the admiral’s talk was the ensuing

Q&A period, which he seemed eager to get to, and which might explain the

hasty quality that his talk displayed: little substance, but lots of fast-moving

slides that seemed aimed to get as quickly to the end as possible. And here, as

with even the talk itself, we dwelled mostly on the Grusch allegations and all

of the government miliary, intelligence and security apparatus surrounding it (a

discussion suitably decorated with sometimes oblique, flowery jargon). [At this

point, I veered into a long tangent on the Grusch affair—again!, but decided

for your, the reader’s mental health, to segregate it safely in an entirely

separate post here.]

Occasionally, the focus in Gallaudet’s talk and subsequent

Q&A shifted to the other two witnesses called to testify at this bombshell

public congressional oversight hearing: Lt. Graves (who gave the keynote at

last year’s AAPC) and (ret.) Cmdr. Fravor (who has yet to appear at an SCU

event – maybe he’s been invited to other UFO/UAP conferences?). That the

testimony of either Graves or Fravor at times only seemed like the

second-fiddle is curious, and maybe it’s worth dwelling on this for a moment.

If only symbolically, the set up we faced during the hearing was interesting,

telling even. Grusch is the central witness, because of the gravity of his

claims; on either side are Graves, whose testimony involves recounting what

many pilots under his command have had to deal with – near-misses with bizarre

UAP, and Fravor, whose testimony recounts what he himself witnessed, along with

several of his squadron crew: the now-famous “tic-tac” zig-zagging around a

roiling ocean, noticing his approach, and then darting off (at about

210,000mph) to Fravor’s classified rendezvous point. What Graves and Fravor provide

for the Grusch testimony is context: yes, the UAP we saw were real objects;

they moved in ways not readily explainable; their flight capabilities appeared

to far exceed that of any known human tech; ergo, either some gov’t has tech far

in advance of U.S. assets, or some UAP are nonhuman tech. And so if

some UAP are advanced nonhuman tech (of the sort witnessed by Fravor, or

reported on by Graves from his subordinates’ testimony), then the testimony of

Grusch is not entirely wildly unbelievable; maybe some of these objects have

crashed and have been recovered. At least, this seems to be the (surface-level)

symbolic implication of the hearing’s witness positioning…

If that’s so, and the very order of the witnesses called to

offer their testimony was a rather deliberate mise en scène, then we

have to wonder: How much of the hearing was orchestrated (don’t want to say staged

exactly), with the characters positioned quite deliberately, for effect? It

doesn’t help when the vociferous and seemingly ubiquitous Jeremy Corbell talks

as if the hearing

was his baby (for him the admissions are in the interests of

“full disclosure”), feeding into the belief that the hearing was far from an

impartial, truth-seeking inquest, but a bit of political theater at the expense

of the true-believer crowd…

But we digress (again I had to resist including an even

longer tangent for the sake of the reader’s sanity). Aside from insights into

the inner working of the intelligence community, and other parts of the DOD (to

the extent, of course, that Gallaudet could even comment on anything here,

since he himself has certain security clearances that bind any of his assertions),

nothing much new was learned. I mean, we started out at the beginning of this

talk in the zeroth setting of rational epistemic indecision (to repeat: since

the material basis for Grusch’s allegations relates to entirely classified

disclosure-discussions, documents, etc., none of that material is accessible by

the scholarly community at large for independent assessment regarding the

veracity or cogency of the claims, documents, photos or anything else to which

Grusch alleges to have been privy). And by the end of the talk, we remained

at that same zeroth level. Neither Gallaudet’s discussion, nor the

breathlessness of the n-th tweet, nor the sum over all podcasts,

self-appointed commentators, news follow-ups, op-eds, letters-to-the-editor,

interviews with the journalists on the beat, or rebuttals from Pentagon

officials … none of this really changes our – i.e., the general public’s –

rational epistemology regarding Grusch and his allegations. But that’s probably

not why Gallaudet was invited, anyway, since SCU started to plan for their

conference a few months ago – even before the early June news bomb from Kean

& Blumenthal that broke the story for The Debrief. Still, I wonder

why the rear admiral was assigned the dignified slot as keynote, and then why

he didn’t supply the SCU’s conference-goers with a robust keynote talk worthy

of the attention of serious-minded UAP researchers. For all the heft that a

figure such as Gallaudet brings to the affair, it was belied by his actual

intellectual performance. It’s a reflection of the very deeply inchoate state

of affairs in anything like an academic field called “UAP Studies”. That field

doesn’t actually exist as yet, and we struggle to bring it into being.

Accordingly, I suppose you’re going to find this kind of content inconsistency.

But we press on.

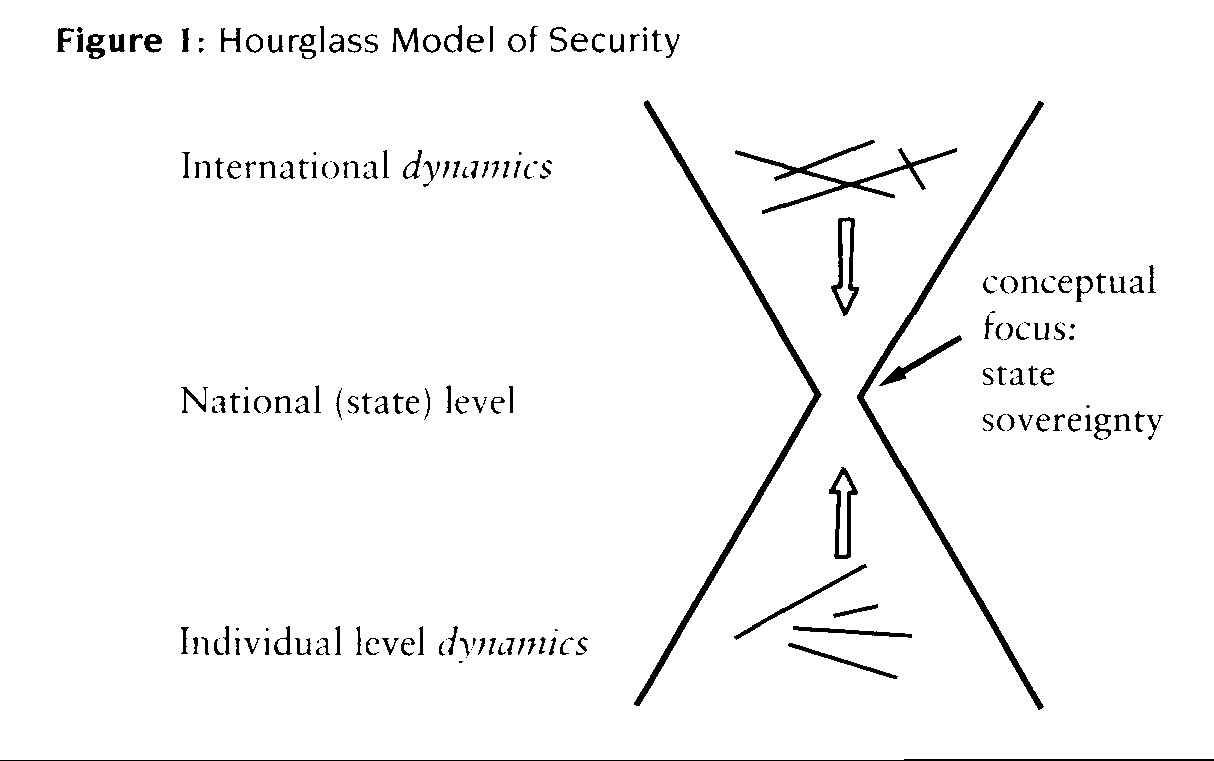

The process of “securitization” is a well-studied phenomenon

in International Relations (it may be central to that discipline). As the

definition informs, “securitization” is a complex strategic process, internal

to a nation state, whereby it seeks to convert some subject, of initially general

political concern, into an issue of “security”—national security, of course.

This process of transforming some subject into a security matter allows the state

to bring to bear its national security and defense apparatus, creating policy,

infrastructure, strategic planning, etc. in an effort to mitigate the potential

threats that may derive from or arise out of whatever is the significant

content of the subject it seeks to securitize. In the case of UFOs, of course, the

situation is curious, since by its nature we’re dealing with a disputed reality—or

rather, a complicated one that mixes mistake, misperception, hoax, with something

there that might really be of national security concern (witness the recent RAND

report, which can in effect be read as a strategic recommendation for the

government in its attempt to securitize the UAP). What Inbar is very

much focused upon—quite significantly, conceptually and philosophically in my

view, though I’m no expert—is the imbalance in the scholarship surrounding this

process of securitization. The focus in the scholarly literature, she contends,

is on when securitization is successful; very little concerns when it fails.

Thus the implication (if I might opine here) is that we have a very imbalanced

understanding of the process itself—indeed, if we don’t know what failure is,

we won’t be able to perceive the structural or even strategic limitations of an

attempt to securitize something. This has, I think, important practical

implications, if only for policymakers and those involved in the material

processes of securitization, for, not knowing the nature of securitization failures,

we don’t know what exactly to recommend on possible subjects of (successful) securitization—we

don’t know because we don’t clearly know why something failed to be

securitized. If all we know are successes, then we’re effectively always guessing,

and muddling through with no clear direction—stuck in: maybe, let’s try

this, let’s try that. So this, then, this gets to an even more fundamental

question: what are the conditions under which something can be successfully

securitized? All we know from the literature are those cases where it succeeds,

not when or where it’s failed (it’s not studied), so, in a sense, we don’t

really know what securitization is—just when it has worked. In other words: we

have “techne” but no “episteme” (to use the ancient Greek epistemological

distinction some readers might be familiar with), know-how without knowledge per

se.

In any case, maybe I’m wrong here and this really doesn’t

amount to a worry, or even to the most important worry, but this was a concern which

prefaced Inbar’s talk. In order to examine the process of securitization of the

UFO (or UAP, rather), which she argues began in earnest with the ODNI report in

2021, she examines the structure of the discourse surrounding UAP, as it

appears especially in the news media, to get clues about how exactly the

process is in play for this subject. It is, as she describes it, a “discourse

analysis”. I wonder, however, if a discourse analysis of news media is the

right focus—but for all I know that’s how one begins to study securitization,

or it’s an approach unique to Inbar herself. Shouldn’t one attempt an analysis

that balances discourse in media—which is external to the defense and security

apparatus that enacts securitization—with discourse internal to those

agencies which are directly involved in structuring the securitization? I also wonder

if the periodization she’s adopted for when securitization begins is well-motivated:

surely securitization has been attempted (perhaps abortively) ever since

the UFO phenomenon broke out during and after the Second World War. If

anything, what we see with UFOs (now UAP) is periodic securitization:

starting and stopping of the process. Perhaps this adds another dimension of

uniqueness and complexity to the securitization of the UFO/UAP (indeed: perhaps

the shift in name is itself structurally significant for securitization, in

that it indicates important shifts in attention, perspective and perception). Inbar

also concerns her study with the aspect of taboo that functions within

the discourse around UFOs/UAP—and here she cites the seminal Wendt paper, who, as it turns

out, is one of her Ph.D. thesis advisors. It was an excellent, and

academically substantial talk, I thought. Not like the keynote.

Following the Griffiths presentation, was a talk by one of

the Galileo Project’s student researchers: Abigail White, who’s gained some

notoriety through the Ryan Graves (uneven in my view) “Merged” podcast. While her

story is a sensitive recounting of her “journey”, I found the talk to be very

much inappropriate for a conference on something like the scientific study

of UAP. I mean, the talk had no real content to offer the community, besides

a self-portrait of a young researcher just trying to figure out where she wants

to go next in her career. What was really odd about the whole thing was that, almost

as an afterthought, she admits she won’t really be pursuing UAP in her

upcoming Ph.D. research studies! Or at least that’s what I thought I

heard. So what’s the lesson from this self-portraiture? In what content

relevant to the conference there was in the talk, it was mostly a general

survey of some of the architecture of the GP’s multimodal observational “suites”,

which range from modestly-priced smaller apparatuses to much larger, and pricier,

stationary systems. But mostly this part of the presentation was meant to

explain where she worked on the project and what instrumentation she was

particularly concerned to work with. I mean, it’s interesting and all, but I

thought it wasn’t appropriate to go personal journey on those in

attendance. Maybe it’s a generational thing…

Next—and we detect a clear theme here—was another student (Robin

Schaub), offering a much more substantial presentation on a reporting and

analysis system being developed and deployed at his university: Würzburg, the

homebase of Prof. Dr. Hakan Kayal (whom Schaub’s working with), who is one of

the most important, serious, robustly academic scientists involved in the contemporary

effort to study UAP scientifically (in Germany, no less—a country that suffers

even more from the debilitating taboo that, as we know, has beleaguered attempts

to study UAP seriously). The system Schaub detailed is a project of a

UAP-focused group at Würzburg: “IFEX”. Auf Deutsch, the name fully spelled out

is: Interdisziplinäres Forschungszentrum für Extraterrestrik, or in

their preferred English vernacular: Interdisciplinary Research Center

for Extraterrestrial Studies. (One might pause to complain about the “extraterrestrial

studies” here, but we have to remember that part of their focus, being lodged

within a space sciences program at the university, is well, extraterrestrial:

things outside of and beyond the earth proper. (It’s all spelled out in

detail on their website, linked supra.) That, and the association was

formed in 2017, just as renewed attention, and scrutiny, emerged for UAP.)

What was curious about Schaub’s presentation was that he

positioned it in relation to an existing system employed in France—but which he

only mentioned in passing, revealing a lack of understanding of what exactly “this

system” is. I presume Schaub was gesturing towards the GEIPAN system. If that’s

so, then it’s unsurprising he doesn’t know much about it, because GEIPAN hasn’t

exactly gone out of its way to detail their system, or provide much insight for

non-French speakers (which, unfortunately, is most of the world; English is very

much the lingua franca today—yes, with all due irony and respect to Français,

which indeed had that status, sort

of, some centuries ago, when the cultural imperialism of empire wasn’t so totalizing).

It’s a tragedy for current UAP research, but it’s part of a general phenomenon I’ve

noticed (perhaps explained by the persistence of the taboo Pincu worried about

in her talk): the lack of UAP-related research contained in searchable databases

scholars regularly access. Anyone, like Schaub, just starting out in this area has a monumentally difficult challenging (needlessly so) in finding, studying, and then incorporating

the results of past work immediately relevant to their own. It is an elementary

but importantly preliminary exercise to engage in a thorough literature

review before one begins to develop their own work in a given discipline or

field. For UAP, not only is there really no field as such—but the work is (therefore) scattered amongst publications in already-legitimate fields or disciplines, or

embedded in what Prof. Watters of the Galileo Project has

recently called the “gray literature” of uneven quality, sometimes

questionable integrity, and therefore of limited or uncertain scholarly usability

(certainly not something that can be uncritically cited as authoritative—an enduring

and perhaps under-addressed methodological quandary vexing UAP scholarship

going forward).

The GEIPAN system provides two things: on the front-side, there

is a place

to report your (or a) UAP/UFO sighting/encounter/incident—they ask you to “testify”

(but the website is stubbornly resistant to English translation). But on the

backside, as I have come to learn, there is a very sophisticated UI for the investigative

team (though it could be a single investigator working on a case-of-interest—the

COIs). And it’s here that the process really begins, from initial report

(uploaded by the witness(s) or manually entered by GEIPAN), follow-up (after a

kind of triage system), to the software-system-generated set of hypotheses attempting

to offer a possible explanation for the sighting—ranked in a clever way,

according to two dimensions: “robustness” and “strangeness”. The suitably analyzed

COIs are at some point shunted over to a “college of experts” (sans periwigs

one assumes) to take a (presumably well-informed and educated) vote on

how to classify the case. And it’s their system of classification that, while

of course not perfect, is (or should be) a model of what needs to be happening

(attention: AARO … let’s not reinvent the wheel). There are four classes into which a UAP

incident case is put: A, B, C, and D. The A’s are nearly proven to be

something known; the B’s are those that are shown to be probably

something known. The C’s are those cases for which there is lack of reliable

data, and so the cases must remain undetermined. Whereas—and here’re the

cases of most interest to those of us who want to get down to scientific

and scholarly business—the D’s are … and please let’s pay attention to what GEIPAN

is saying here … those which, while having sufficiently reliable information

and adequate data on which to make a determination, nonetheless fail to be understood

as containing a report of a known phenomenon of some kind. The D cases are

further subdivided into D1 (“strange”) and D2 (“very strange”). It’s the D’s

that are passed on for further investigation—forensic follow-up. They are thus,

in effect, cases that are submitted to field investigators for reevaluation.

Thus, a D might be converted into A or B (presumably the fact that it’s deemed

a D case means C—cases that lack sufficient data—is no longer an applicable label).

What GEIPAN does not do, after looking into the D’s,

is research further to see what explanation would work, once the reevaluation process is complete. That’s the point

at which a science begins, for these cases are those which would seem to

suggest “truly new empirical observations” (to use Hynek’s expression, which I’ve

come to like).

Schaub shows us that they’ve got some part of this kind of

thing in the works, and partially up-and-running. But what’s importantly

different here is that suites of observational equipment will be part of the hypothesis-generation

mode of the initial analysis of the UAP case data. This is important, since it

will begin to integrate live, empirical data that can be used to create a

richer informational tapestry, from which one can derive more secure analytical

conclusions. Indeed, in so doing, we begin the process of converting the data from

mere UAP report to factual (and verifiable) data on the UAP itself. (Let’s not

forget Vallée’s important proviso, which haunts the science of these phenomena:

we deal not with the UFO, but with the report of the UFO…) But there was

one thing I caught from Schaub’s talk that was potentially worrisome, and that’s

the stated desire to “delete the role” or participation of the human subject in

the UAP incident. I think he means to mitigate the potential biases introduced

in the testimony supplied as part of the data on a UAP incident. One cannot “delete”

the human from anything—for then we’d have nothing of meaning or significance on

which to work. (This is a characteristic concern of the humanities in dealing

with how, methodologically speaking, the scientists propose to go about studying

UAP, and why humanists and social scientists have to be involved in some reciprocally

significant way. Thus we bring the Society for UAP Studies to bear…)

After a short break, we found two final events: one more talk,

related to the work members of SCU itself were conducting (let’s not forget SCU

is in essence a think-tank), and a closing “AIAA” panel which provided a series

of (shorter) pre-recorded talks derived from the three papers

accepted by and presented to the American Institute of

Aeronautics and Astronautics.

Finally, the panel. The three, very high-quality, substantial

(and technical) talks here were:

Peter Reali’s “System Study of

Constraints for the Creation of UAP Electromagnetic Signature Optimal Detection

Systems.”

Ralph Howard’s “FAA Unmanned

Aircraft Systems (UAS) Sighting Reports: A Preliminary Survey.”

Tim Oliver’s physics-heavy “Aerodynamic

Interactions and Turbulence Mitigation by Unidentified Aerospace-undersea

Phenomena.”

Only a few scattered comments are in order, as I’ve

doubtlessly already taxed the reader’s patience (and need for sleep).

What Mr. Reali talked about was work done on examining just

what it would take, across the board, to really get optimal detection rates for

UAP, given what we know about their frequencies of occurrence as a function of

geographic location. Just how much geography does one have to cover, to get

optimal (EM/optical) detection? That’s a hard question to answer in detail, though

it’s not hard to set up the problem itself, as Peter does very naturally, and

with obvious competence. The work is practically relevant—he’s an engineer,

after all, so practicals (like, so how much are we talking?) have to

matter at some point. The talk breaks it down: there are so many geographic

regions that need to be covered, and with a certain swath of aerospace able to

be scanned, relative to the instrument-specific specs (that are a necessary

factor to consider here), this determines the total number (and type) of

systems needed. And you can put a price tag on that (it’s in the millions for

each subsector—but not insanely unreachable budgetary goals, esp. considering

the total U.S. national defense budget … lol’s all ‘round: we can do this if we’re

serious about it).

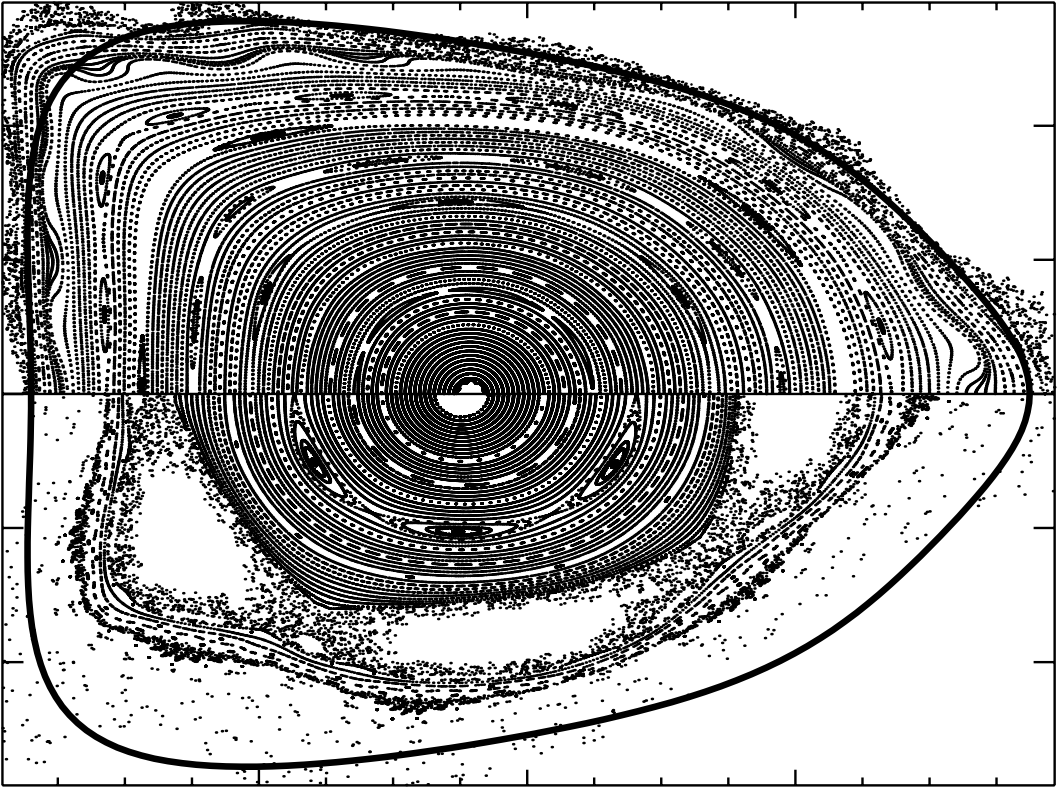

I was sadly distracted by house-matters during Ralph’s talk, but I did manage to catch the bulk of Tim Oliver’s (well, ok, I’ll admit to being enthused about any physics talks related to UAP). What we got here was a substantial study of one of the hallmark phenomenological features of many UAP reports (or at least, those of a certain type): the observed and sometimes radar-recorded rapid acceleration to extreme (hypersonic) velocity of apparently structured objects but with no discernible sonic-boom or other—expected—thermal signatures. Is it possible, the talk asks in effect, to model this with known physics? Apparently, it is: you can mitigate the propagation of the shock wave or other thermal energy through the generation of a surrounding force field (of some kind) which acts to counter these effects (basically, of a rigid object passing through a fluid). Or so proposed the perhaps obscure but significant UFO researcher Paul Hill (NASA scientist no less) in a little-read tome entitled Unconventional Flying Objects: A Scientific Analysis (1995). And this was Oliver’s theoretic starting point (practicing classic scholarship in the process: starting off where others have left off).

The approach adopted by Oliver, following Hill, uses computational fluid dynamics (CFD) to create the basic model for how the hypothetical field of force behaves with respect to the surrounding fluid (which is what the media, through which the UAP would travel, are conceived to be—at least for the purposes of this analysis) in order the get the right effects to work out that would be needed to suppress or nullify the stuff we don’t but should observe (sonic-booms, etc.). But what is (or would be) the nature of this hypothetical force field? In an analytical tactic that goes all the way back to Newton himself (who similarly just looked for the mathematical/physical form the force we now call gravity must take, which acts in this case universally on all material bodies), Oliver in effect splits this problem into two, independently tractable ones. First find the form that this field-of-force must take in order to achieve the desired effects (mitigating sonic-booms, etc.); then ask what physical mechanism or process could create such a field with the required properties. As far as I can tell, Oliver has completed the first part of the problem, and the second one still remains an open question (though I am no expert, so my claims here are tentative).

So then, first, following Hill, we can simply ask: what form should a counteracting force field take (what must its mathematical/physical properties be), in order to cancel (or otherwise nullify) the resulting shock-waves (and other thermal effects due to frictional forces acting on a rapidly moving rigid body through a fluidic medium)? In the introduction to his paper submitted to AAAS, and presented to them (a paper not yet peer-reviewed, but just released on the SCU website), Oliver writes that (and we quote him at length):

“Hill proposed that

fast-moving objects can manipulate the surrounding flow field by imposing a

force field. This method, which draws on potential flow theory, involves

equating the force field potential to the kinetic energy associated with the flow. The engineered force field can

theoretically counteract the kinetic energy of the flow, resulting in a

constant density, constant pressure flow without energy losses. When correctly

formulated and employed, the force field should produce speed-independent flow

patterns that apply to both compressible and incompressible fluid flows.

So, once the details of this flow structure are worked out (and that constitutes the bulk of Oliver’s analysis, at least in the paper), we can then move on to part two of the problem, which involves a question about what the exact nature of the force field itself could be, as in: what could the physics of this field be? What know what form that force field must take, and the properties it must exhibit, but is there anything physical that can satisfy these theoretical demands? Presumably, those finer details (like the particular equations that would describe the behavior of the force field, as Hill requires there to be, which surrounds a UAP and is supposed to enable its evidently smooth, shock-free travel) could be derived from the principles of magnetohydrodynamics. MHD, as they call it in the biz, seems to be an increasingly popular alternative conception to how exactly the UAP can move so fast. That is, MHD is a popular alternative to even more speculative (and conceptually problematic) accounts of UAP kinematics using what they call “metric engineering” but which you probably know as “warp drive” (yes, the Star Trek thing). Maybe we can exploit this same hypothetical MHD propulsion mechanism to also explain the absence of sonic booms? (At least, this is the question I would pose.) In other words, the question here is: could a suitably engineered (magnetohydrodynamic) plasma do the trick? If so, then we might be able to come up with a unifying explanatory model of UAP kinematics, since if the plasma is also related to the propulsion (an MHD drive of some kind), then we have an idea even of the architecture of the technology that has been engineered (presumably by whatever intelligence(s) is(are) responsible for these evidently structured objects) for trans-medium (and especially atmospheric) travel at extreme velocity (greater than Mach 5; for example, the tic-tac Fravor describes appeared to move at over 200,000mph and that works out to be, in air, a cool Mach 260 or so. I mean, is that even hypersonic anymore?).

In my personal view (which is not necessarily endorsed by Oliver or part of his paper’s analysis), according to this CFD + MHD model you’d basically be dealing with the interaction between two fluids manifesting different physical properties (electromagnetically active plasma and air, for sky-bound UAP, or water, for submerged ones), so the key is in understanding exactly how the (proposed) MHD plasmoid surrounding a (hypothetical) UAP interacts with the rest of the medium-of-travel in the UAP’s immediate physical environment. (I suppose the creation of the plasma would at some point entail, at least along the surface where the plasma interacts with atmosphere, ionization, and that might be useful in mitigating the thermal effects, sonic-booms etc.)In any case, I don’t want to get ahead of what Oliver has very carefully worked out (especially since I’m not a physicist). In his conclusion, he writes (and again we quote his recently-released paper at length):

“The[ese] research findings

highlight the significant stabilizing effect that an applied force field can

have on flow field pressure

and flow patterns, particularly in compressible cases. This suggests the

potential to utilize an engineered force field to neutralize any pressure differences that may

arise within the flow field when objects move rapidly through

compressible and incompressible media. The study

demonstrated that the force field strength would need to be

proportional to the square of velocity to achieve the

desired effect, and the form of the resultant pressure field is largely speed-independent.

“To implement this approach,

the force field strength could be adjusted according to the craft's velocity,

allowing it to be

used across a range of speeds. However, challenges may arise at higher speeds

due to increased misbalanced forces. Rapid maneuverability would necessitate rapid

changes of field strength, and radial movements of the object

would necessitate changes in field form. Furthermore,

when passing through atmospheric pressure disturbances, continuous monitoring and adjustments to the force

field's strength and shape may be necessary.

“Despite these concerns, the use of an engineered force field, whilst speculative, could offer a potential explanation for the lack of interference of fast-moving objects in compressible and incompressible media, potentially preventing the formation of shock waves and aerodynamic heating for objects traveling at extreme speeds in the atmosphere.”

With this, Day One of the 2023 AAPC closed. I went to sleep that evening very happy in the end, after having gotten very cranky with the keynote and with some talks that were, in my view, inappropriate or otherwise insubstantial additions to an evidently professional and scientific conference. I was therefore enthused about and very much looking forward to Day Two.

Which I’ll get to in my next post...

Comments

Post a Comment