Reenchantment of the World & The Romance of Transcendence: Archives of the Impossible II. Part Two.

The 20th century grew up under the specter of

oppression, as it became clear in what ways “Progress” (that fateful moniker of

the age) was purchased, at what cost advancement was gained as humankind

was lifted from its thrownness in nature – an infant incapable of

extricating itself from its given conditions – to a position of self-reliance,

self-determination, and self-creation. Indeed, Nietzsche, the great

celebrant of human potential (as Wille zur Macht) dies in August of

1900, the year we see Freud’s publication of Traumdeutung, The

Interpretation of Dreams. Had the ironworks, and the factories that were

their home, producing from the raw materials of the earth new materials for

building the Modern World of steam, speed, and smoke … had they pressed down

upon Man and stifled his spirit? Was his being thereby lost, forgotten,

displaced, exorcised from the material world to the airy world of the

immaterial (what was that late 19th century fascination with the

spirit world, with its vain attempts to materialize it?) What was

‘spirit’ after all – not the abstraction of religion or theology (itself already

a kind of obscuration, according to Nietzsche, as body was forsaken for the

smoke of an immaterial ‘soul’), but that which is the temple of the body (to

invert Christ’s formula)? Both Nietzsche and Freud – and many others: Marx,

Durkheim, Weber, Simmel, … the grandchildren of the somewhat anxious

post-Enlightenment – looked askance at what was eventually called ‘modernity’

to see a high cost in this newfound ‘progress’. For Nietzsche, what replaces the

necessity for self-building in the (then-nascent) modern world is the blinking

a-hedonic indifference of die letzte Mensch (the “last men”), whose

needs are taken care of and who do not therefore have to build themselves into

something of solid, self-reliant standing (his thinking here quite dependent on

the American “transcendentalist” Emerson). For Freud the displaced, arrested

erotic fulfilment that comes from the imposition of the socially necessary

demands of the super-ego, curtailing pleasure in favor of what is practically

required by the modern system in order that it function (a kind of rational

irrationality): the erotic gets restrained, sublimated, leaving man frustrated,

anxious, neurotic. “We’ll get to that later, after work” is perhaps the

death rattle of eros…

Of late Kripal has taken to Nietzsche, a thinker who, he once

told me, he had sort of overlooked, able to see the radical philosopher only

through the distorting lens of academic summary or outline. It is to Nietzsche

that his concept of the super-humanities (perhaps somewhat obliquely) is ultimately

indebted: Übermensch could be translated (poorly) as super-man. But then

there’s Hollywood. And before that the Nazis, in their once-successful

appropriation of the Nietzschean philosophy of Wille zur Macht.

Nietzsche surely believed in some kind of potency of

which human beings were capable but had not expressed (because of social,

cultural and conceptual repressions from without). But what are the conditions

of its realization? Does it require a metaphysical transcendence? What

is metaphysics (the greatest of the philosophical questions)? Does this require

a movement from materialism to something else, and in which case is the

transformation merely conceptual or intellectual – is it just about

‘paradigms’? Surely that wasn’t what Nietzsche meant at all. All this is

second-order; Nietzsche was first- or even zero-order: it was an unrealized

potency of the human body as a “body-spirit” – and that has nothing to do with

materialism or idealism, or any ‘ism’ the mind (as a “believer”) might adopt.

So perhaps we cannot appreciate the import of Nietzsche’s thought without the

kind of deflationary metaphysic of the so-called Existentialists, who tried to

refocus on doing and creating, rather than “thinking” per se (and yes,

this sets up a dichotomy about which we ought to be very cautious—if not

outright skeptical).

If there is anything to what I like to call (somewhat tongue-in-cheek)

“mystical atheism” or “spiritual materialistic irreligion” then it’s found here,

in what Nietzsche called the “reevaluation” and later “transvaluation” of all values:

a spiritually treacherous but fruitful movement from ‘mind’ into the body (but

not ‘body’ as opposed to the mind). If there is any ‘transcendence’ in

Nietzsche’s concept of Übermensch, then it is one that is well within this

world. It is therefore anti-Platonic, anti-theological, non-metaphysical (in

the sense of isms like materialism, idealism, etc.). It is a kind of

“nomadology”, horizontal as opposed to vertical, “rhizomatic” as opposed to

“arborescent” if we want to borrow the terminology of Deleuze & Guattari’s Thousand

Plateaus. It seeks surfaces, and never sees depths under them (an

exuberance of the surface!). If there is an ‘unconscious’ then it is precisely

that which lives upon the surface(s) of the body (was this not the basic critique

of Deleuze and Guattari’s first text, Anti-Oedipus?). This is

non-transcendence. Nietzsche refers to “überwindung” or overcoming of

something in the world, in the body but never outside or “beyond” it. We can

imagine an echo of the Confucian admonition here: leave the dead beyond to

take care of themselves. What is beyond the body is death, so leave death

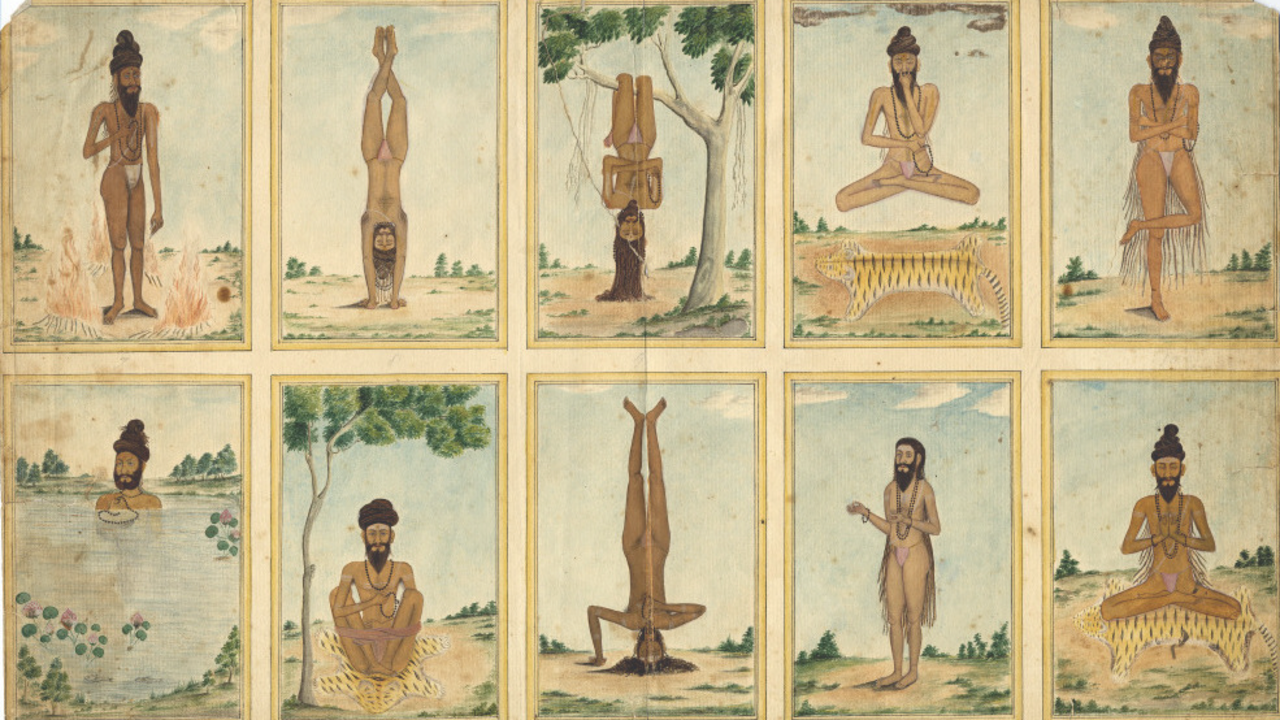

to death; take care of the body! This is more zen than tantra or lama.

It is the quietude of the morning doves with their squeaking wings in the

breeze, than the rapture of the yogi (Rajneesh-style).

What, then, were we witness to during the Archives of the

Impossible, which cut no dissimulation by adding “transcendence” to one of

its trans-es? Surely, it was an example of this trend, slowing growing

since the dawn of the previous century, of – and what should it be called? – the

“Reenchantment of the World”, the self-conscious reversal of a structural

(perhaps sociological) fact discovered by Weber, which he called die

Entzauberung der Welt – the disenchantment of the world.

But it was curious and remarkable that Archives II

began with two talks on the UFO phenomenon: an “outside” (historical) and

“inside” (religious-cultural) view of it. Because it is clear that the UFO

phenomenon itself (at least from an historical perspective) is caught up in a

larger socio-cultural and historical phenomenon; the Europeanist and Historian

Alexander Geppert calls it “astroculture”. And it is very much concerned with

transcendence – but of the off-worldly, rather than this- or other-worldly

kind. As such it makes striking contact with what Bruno Latour has noted is the

emergence of a new coordinate space of sociopolitical possibilities: the

Earth-bound (Gaia-centered) v. the off-world-bound (though we should note that

the gospel of transcendence, starting with the “space brothers” of Adamski –

gospel we find repeated frequently in contactee or abductee narratives – is

very much concerned to admonish human beings in their this-worldly

stupidities).

At our late stage of civilizational development, in which the

world is no longer the infinite expanse of possible nomadic, lateral wandering,

in which nowhere is enough of an escape, this logic of permanence of place necessarily

takes the whole world as that towards which nomadic liberation moves in

search of the freedom of the human spirit. Hence the logic of the off-worlders

Latour worries about: there’s no where to go except outer space (or inner space—and

we’ve had enough inner, haven’t we?). Is, then, the more profound confrontation

at work in the phenomenon of the “things seen in the sky” which presently is

caught up in the dynamics of an emergent religion of skyward transcendence (is

this finally the Pasulka thesis?), the incipient religion of the “space

brothers” (and sisters?) that form a significant sociocultural layer to the

historical phenomenon of our fascination with the UFO, … is this complicating

the attempt to reach into the empirical (non-mythic) core—the “real” that

fascinates even as its frightens, or deludes? Are we confronted, that is, by a

nomadic phenomenon intersecting our civilizations of place and permanence just

at the moment when the surface of our world becomes inhospitable,

increasingly uninhabitable—necessitating a Planet B?

Our only option, if we confront the reality of Gaia head-on

would seem to be total structural change (induced by a serious alteration in

our relationship with energy and matter, leaving behind our Promethean

impulses), or escape (leaving the miseries of our poor, desolating surface

behind). But why not a third option, the excluded middle: A return to the

oceans? Why not a submergence, descending into the world rather than

seeking an escape from it (off-world)? Is there more intimacy in the ocean, in

water, where light is lost and the body is afforded perhaps more development of

the somatosensory architecture of a diffuse, distributed “mind”? (The octopi

are creatures of extended mind, each portion of their bodies a kind of brain,

or a brain distributed over the surface of their bodies, the eye being perhaps

subservient to touch, smell, taste—or perhaps their senses are configured

without the rigid dominance of the visual which burdens many of the larger creatures

of the land.)

Returning back to the mundane machinations of the UFO, we wonder. With no framework for dealing with the uncanny, it is easy to get lost in a sea of empirically unconstrained speculations. It’s this, I believe—the lack of empirically constrained frameworks for capturing the uncanny—that constitutes the foundational problem in UAP Studies, and in “ufology” more specifically. And it is this that forms the major division in that subject—not the vulgar distinction between “nuts-and-bolts” v. the “woo”. The former simply tries to force the uncanny remainder of the UAP into existing but problematic frameworks (or drops it entirely—falsifying much of the UFO experience in the process), whereas the latter exit them all together. But Archives II offered some academics the chance to try to bring the speculations to some kind of more definite articulation, to situate the uncanny, the paranormal in something that offers inner conceptual coherence, as strange (to us) as the core phenomena might remain. But what are these phenomena of the uncanny—Kripal’s “impossible”? I am suggesting that a mere framework is not enough until it is empirically constrained, situated within the realm of nature. Or what Spinoza would have called, perhaps, Deus sive Natura (i.e., “God, or Nature”). The “divine” for him was an “infinite substance” which had an infinite array of expressions, a plurality that would only be more consistently thought by William James centuries later but which still yet remains external to the empirical disciplines, and whose formal implications have yet to be rigorously developed and deployed for the purposes of surpassing (and finally overcoming) the matter/mind break complicating and debilitating the sciences (at least in their function of providing explanation and understanding. I say this, but of course there is a rich tradition of making an attempt to elevate these reflections beyond mere critique, to achieve a new (empirical) logic of the specific that is neutral with respect to the persistent division of matter and mind. We might refer here to the rigorous work of Harald Atmanspacher, for one example with which I am familiar. It is this kind of work that can obviate the slide towards idealism that could be detected amongst many of the academics (and other speakers) at Archives II. (I will have occasion later in this review to revisit this issue, and to submit my own response which was prompted by some of my colleagues’ interventions in a discussion I had recently with them.)

I am writing these reflections in the wake of the increasingly

confusing, titillating, frustrating and ultimately epistemically indeterminate

“disclosures” of the apparently high-level whistleblower, David Grusch. As the

world already knows, Grusch ostensibly spilled the disclosure beans in a

bombshell article for the Debrief, penned by the Kean/Blumenthal team that had

exploded the subject (of government investigating UFOs) in 2017 in a well-known

article for the New York Times. Overnight, we were thrust into a miasma

of hearsay, the he-said, she-said of the typical Elizondo-style insider who

insists on (and in this case purports to disclose, in detail only to

Congress and its Inspector General) the existence of highly secretive,

ultimately classified (and compartmented) data and information indicating the

U.S. government’s possession of “nonhuman technology” (fragments or “intact

craft”), even (it would seem) bodies of nonhuman creatures who piloted some of

these technologies. We’re told of long-standing “reverse engineering” programs,

intentional downing of some UAP, and even malevolent interactions between human

military officers and nonhuman intelligence in which the officers were either

harmed or killed in the process. And as with much of these insiders, the drift

towards speculative hypotheses is irresistible, as if these “disclosures” are

not enough on their own. In his interview with Ross Coulthart, and as recounted

in a recent article for the French news website Le Parisien, Grusch,

who admits he has no first-hand knowledge of the material evidence he says exists

(he claims access to reports and the testimony of others), opines that the

objects/craft “could be extraterrestrial” or “something else, from other

dimensions as described by quantum mechanics”—quite despite the fact that

quantum mechanics neither requires nor deals with “other dimensions”. Maybe

he’s thinking of a particularly controversial interpretation of the

theory which posits the existence of parallel and constantly-forking branches

of the wavefunction describing the evolution of the whole universe? (But in

this case, descriptions of processes in space and time—with three spatial

dimensions, plus the one for time—evolve in a higher-dimensional state space

which must be projected into our ordinary spacetime. But these higher

dimensions are just facts about the representation space, not about the world

itself, which does just fine with four dimensions.) He claims to have “graduated

in physics” but offers only a stilted articulation of quantum theory (which in

any case is somewhat interpretationally confused), so it’s hard to form of

judgment here. (The landscape of interpretation of quantum theory requires a much

longer discussion to be sure as there’s lots of controversy and disagreement

among scholars—so it’s best tabled for the moment.) What I suppose this

demonstrates is that the uncanny is an occasion for the derailment of thought,

and in the current context of “disclosure” is just radically unhelpful. Even if

we could accept the disclosures of Grusch, given that our understanding of the best

physical theories we have—the gravitational/spacetime theory of Einstein, and

the quantum theory of matter—is at best tenuous, especially if we try to

coherently relate the former to the latter, whatever the government does

possess is likely to be strikingly incomprehensible. Surely not understood to

the point where it makes much contact with physics (or science) as we know it.

If even the known physics we have is either incomplete or inadequately

understood, then surely our understanding will be even worse if, as

Grusch alleges is the case, we were to come into the possession of nonhuman

technology capable of engaging in the kinds of kinematic acrobatics we have

evidence for in some of the more well-documented UAP cases on record. We

therefore must leave these allegations, as arresting as they are, alone. At

least for the moment…

In contrast, the range of the impossible under consideration

at Archives II, from Day 2 to 3, draws on conceptual (and experiential)

worlds that would seem to be incompatible with modern science. Seem—but

wherefore the incompatibility? The stock answer to this simple question (I

mean, does vocalization enable the crystallization of material forms, as we

considered in Prof. Biernacki’s walk through the philosophical intricacies of

Indian mantra soteriology?) is something about the “materialism” of

science, about its exclusion of mind from the material world. But what if we

imposed, out of democratic concern for cognitive balance, a principle of

critical symmetry: if science might not grasp the non-materialistic

possibilities of reality because of its materialistic biases, then shouldn’t we

say that (equally) the Vedic or Buddhist philosophies of India might not grasp

the detailed structure of (material) nature because of its bias towards the concerns

of spiritual salvation (these traditions are, after all, structured by a logic

of soteriology)? And if these non-scientific soteriological traditions

have approached nature through only the lens of “moksha” (or nirvana—the

soteriological or salvific end goal, the structuring telos of these

traditions, which we might call liberation), then haven’t they in effect

distorted or even complicated the structure of nature (which we

might seek to free of such narrow concerns). We might say (that is) that

because science has inadequately incorporated the dimension of mind into its

conceptual architecture, then matter is also distorted in the process.

Yet, by our principle of critical symmetry, we say that because of the

soteriological orientation of these traditions, mind has itself been

distorted because matter is inadequately grasped and assimilated by them.

If “materialistic” science doesn’t have the complete picture, well then neither

do the “idealistic” (soteriological) systems of the Indian traditions. If matter,

then, is only partially grasped well by science (with mind awkwardly dangling

as an outlier), mind is, too, only partially grasped well by these

philosophically sophisticated soteriologies of India (with matter dangling as

an outlier, an adjunct to something “higher”). As we criticize science for its

materialism, we risk failing to perceive the shortcomings of those idealistic traditions

which seem to provide a more subtle accounting of mind, but which (perhaps

because of this) fail to perceive the factual structure of matter itself.

Biernacki spoke of a “sun” science, defined in terms of a

capacity to materialize an object from the vocalization of sounds (mantra

is the art of, as it were, spiritually efficacious vocalizations—that is, those

with a liberating power). Apparently, it has something to do with one’s “will”.

But the secret to this power rests with a more general principle which (like in

the Western Hermetic and alchemical traditions) has it that “everything is of

the nature of everything else”. Mantric sounds are the drawing forth, then, of

what is already implicitly present in anything. Not a creation so much as a

transformation of one form into another—because the latter is already found in

the former. This calls to mind the (perhaps obscure) debate in the ancient

Samkya-Yoga tradition (considered one of the orthodox Vedic “darshana” or

philosophical-visionary schools) of whether, when something comes into

being, it was already preexistent in the cause(s) implicated in the process—or

if it is new (i.e., not itself found already there in the cause(s)). A little

paradox ensues, it would seem, if something is truly new; so, we seem to have

to fall back on the view that anything new is just a kind of modification of

what already exists (if something is absolutely new, how could it have come

into being at all—from nothing?). So, we end up with a kind of holographic

principle where, at least theoretically, everything has the nature of anything

else—from one thing to another is just a series of modifications from the one

to the (different) other.

As the reader no doubt can detect, the above reflections in

connection with yogic siddhi are a real struggle for me. And I don’t propose to

make pronouncements here as if I’m an expert. I just am genuinely wanting to

know, to experience, to see, and to think these phenomena properly. If the are

“secrets” of the “inner tradition” or somesuch, then it’s not clear to me that

“materialism” is the real problem, for the deeper structural logic of “Western

materialist science” is democratic openness and replicable transparency of

experimental demonstration: nature isn’t so greedy as to keep her secrets locked

behind all-too-human systems of esotericism. Science is fundamentally

exoteric—and to repeat this has nothing to do with “materialism”. So, the

ball’s in the court of the impossibles…

The danger now is that I’ve gotten distracted, and the review

is falling by the wayside. But let’s press on.

Somehow, I really liked the talk by Dale Allison, entitled

“Comparing Like With Like: The Impossible Jesus and Impossible Others”. He

offered what appeared to be a kind of empiricism of the uncanny, attempting to

suspend judgment about what was gotten through testimony regarding the

miraculous acts of Jesus, as if trying to perceive a moment prior to the

historical accretions of the subsequent metaphysical-theological shroud put

over the face of Christ. But the next talk was another story.

We come to the Rey Hernandez phenomenon, a

cognitive-intellectual disaster zone all unto itself. Talk about a holographic

principle at work: he embodies every fraught aspect of ufology. I mean,

it’s all there: narcissistic egoism; self-selling; the “experiencer” and “contactee”

thing; dubious “studies” that prove this or that; hob-nobbing and name-dropping

the greats. Oh, and then there’s the song-and-dance we’re given about why he doesn’t

have his Ph.D. but almost did. And so, he actually went through the

trouble of listing himself as an almost-doctor-of-something on his first

slide, before, in the talk itself, we were bombarded with a

hundreds-of-pages-long text he’s written (or produced, or whatever it was that

caused it to exist). This is the person who typifies exactly the kind of person

you never, ever want to invite to an actual conference. I just don’t

know why this guy was given the podium—especially with so many actual scholars

and intellectuals who graced us with their presence (Kripal himself, Eghigian,

Finley, Biernacki, the medievalist Barbara Newman, Classical Chinese scholar

Michael Lackner, Sharon Rawlette, and so on).

Best I could tell, Hernandez was there to essentially sell

the audience first on his own importance and books, second on the brilliance

and significance of this “FREE” study of which he was a part, the one that

boasts a few thousand respondents claiming experiencer status of some sort or

other and purporting to reveal something significant about the character of

their experiences. In other words, all we have is a survey, and a dubious

generalization to some relevant population—CE3- & CE4-ers. The study as far

as I know was published in the JSE. It’s trying to provide some

seemingly empirical basis for this claim that drifts around the ufological community

that the UFO experience is positively transformative—something like what

we might call the Mack thesis. But since we have to independent access to these

phenomena which are supposed to be the object-cause of the experiences the

“experiencers” are having, we really cannot tell if these purported

transformations are intrinsically related to the UAP supposedly associated with

them, or whether we can attribute the transformations to the experiencers

themselves—or just to the general psychology of shock. Yes, UAP can be

shocking—and John E. Mack wanted to impute to it something more: “ontological

shock”, a disturbance to your fundamental orientation in the world as a whole.

The idea, I guess, is that closer contact with UAP (and then with beings in

association with them) rips open one’s seemingly narrow ontological-epistemic

field of understanding, and discloses a kind of reality that upends everything

one knows—or thought they knew. That, at any rate, seems to be the narrative.

Again, there’s lots to be dubious about and as I’ve said again and again, this

doubt has nothing to do with “materialism”. It’s just basic critical

thinking: if we have no independent access to or understanding of UAP (or any

beings associated with them), then how can we really understand the significance

of what a certain segment of “experiencers” of these phenomena report to us? (And

to add to the difficulty, which doesn’t begin with Mack but is certainly

extended by him: are we also being told that no “materialist” scientists

will be able to access these phenomena? Or that their failure to see or grasp is

a function of their incompatible worldview? That these phenomena are not even

susceptible to conventional scientific detection? Are these phenomena

not detectable because the scientists have a certain worldview, or do the

scientists have a certain worldview because these phenomena aren’t

detectable? It’s a thorny problem, but let’s not forget that the sciences

are starting to bring their frameworks to bear on the problems here, and we

must wait and see the extent to which they will or won’t fall, change or

modulate in the process…)

For the rest of Friday, we were privy to talks by Colm

Kelleher, of Skinwalkers at the Pentagon fame doing his “from werewolves

and poltergeist hitchhikers to UAP” thing (hey, maybe it’s all there in all

those NIDS/AAWSAP docs, but there’s a simple question, as with the Grusch

allegations: where’s the beef?); German professor of Classical Chinese

Thought Michal Lackner talking about “Divination: An Alternative Rationality”;

and longtime adjunct professor Kenny Paul Smith presenting on his enacting of the

ground-level duty of actually trying to teach undergraduates about all of this

uncanniness that’s out there. The absolute highlight of the day, of course, was

twofold—both presentations of which ended up being rather intensely

personal and emotional.

First, we had the recollections of famed medievalist Barbara

Newman, who for some years was a kind of spiritual companion to a working

mystic, a woman who had this strangely torturous living synchronicity with a

man who’d died but with whom she’d had some kind of relationship. The talk was

made all the more profound because of the earnestness and eloquence of Newman’s

telling of her encounters, which ended with the mystic’s suicide. Very much

present, authentic. The talk was called “‘To Slip Between Dimensions’: A Tale

of Glory and Tragedy”.

Newman’s emotional portrait of her spiritual companionship

took the afternoon plenary slot of the day. It was an immensely eloquent,

sensitive, and learned exploration of a companionship with someone, whom she describes

as a ‘mystic’, operating within a rather different

intellectual-emotional-spiritual landscape. One populated with seemingly

impossible, or at any rate uncanny, nonlocal connections. As Newman recounts,

it was as if the two were acting as “one in another”, bound across space (and

time). Explicating this more exactly, Newman invoked the theological-philosophical

concept of “coinherence”, an idea usually associated with the particular ontological

situation of the Christian “Trinity”. That’s the “three gods in one” idea that

emerged at some point a few hundred years after Christianity arises as a major

religion in the Greco-Roman world. (Scholarship is, if I recall correctly,

fairly clear that in the earliest days, Christ wasn’t really seen as (a) god,

but perhaps as a special appointee of the divine (hence “christos” or the

anointed one) … but eventually so special that, given the ministry

and “signs and wonders” disclosed during and within Jesus’ life, acquired the

interpretation of being the “son” of God, now a “Father” … and hence, we

have a metaphysical procession: out of God the Father follows the Son

(Jesus), and between them the Holy Spirit is manifest as their completeness, this

triune totality manifesting a relation of coinherence with respect to each

of the parts: they exist together with each other, never fully separate or

distinct such that their identities are maintained without erasure, but

nonetheless still maintaining some identity. Perhaps we have a case of identity

in difference. And what’s interesting is that in Christian Theology, it’s

the differences that are stressed, at least in terms of its strong devotionalism

(which, from a comparative perspective, isn’t unlike the popular bhakti yoga

tradition found in the Indian religious landscape—a yoga that has a

corresponding sophisticated philosophical expression). In many ways, this

wasn’t a talk just about one mystic, bearing a relation of coinherence

to her spiritual second. “The human is two,” as Jeff Kripal himself recently

explained in a piece for the journal Mind and Matter, at one point

Newman invokes the African concept of “Obuntu” which expresses the thought that

the individual, the “I”, is really always produced out of the many: “we

are,” Newman paraphrased, “therefore I am”—thus inverting the Cartesian

analysis. So, this talk seemed to suggest an impossible direction in the

very concept, and performance of, human identity. Was this, again, pointed in

the direction of Kripal’s “super-human”? That would seem to be thematically

consistent, as this is the central theme of his current trilogy on the

subject—and he is the conference organizer after all…

A kind of secondary plenary for the later afternoon session was

given in the form of a panel during which we found an equally emotional

presentation by the John E. Mack Institute’s current (and longtime) Executive Director,

Karin Austin (whom I know very well. Indeed, I consider a Karin a friend—one

who knows and respects where I stand vis-a-vie abductions, ontological

transformations, colliding worldviews and the like). It was partly the story of

Karin’s deep personal connection with Mack, where at some point in the ‘90s she

became Mack’s personal assistant, co-residing with him until his sudden and

tragic death in 2004. Karin tells the heart-wrenching story of driving John (as

she of course called him) to the Boston airport, being the last person he would

see from the U.S. It was a bit of a rushed goodbye, she tells us, struggling to

hold back the tears. She leaves us with the image of the back of John’s tweed

coat as he rushes off to catch his flight to London, where, in the suburbs, his

life would tragically come to an end: a drunk driver strikes him as he crosses

a darkened street one evening (Mack’s family would later plead clemency for the

man).

The other part of the story, immediately relevant to the very

raison d’être of the whole of Archive, was Karin and Co.’s

monumental effort to convert Mack’s voluminous personal archives of client

case-files (the bulk of which are from his working with abductees and other

“experiencers”), notes, manuscripts (some left abandoned as Mack unexpectedly departed

for Elysian fields), and other sundry written or collected materials into

digital form (where possible—some material is physical, not informational or

documentary). There were a few hundred banker boxes filled to bursting. The

original project began, Karin notes, with team members somewhat naively

thinking it could be dispatched in a few short months. That was a LOL moment. After

the first few days, we’re told in wonderfully humorous, affable turns of

phrase, Karin realized that there was one important physical reality that had

been overlooked in the way that all novices forget the mundane tedium of the

master’s actual craft (as opposed to the magical final product that

mysteriously obscures the nitty-gritty of material production—how exactly did

Marx put it in Kapital?). Oh, no shit: the staples! Each one has to be carefully

dislocated from the paper which it greedily clasps, originally for practical

organizational purposes but which now, decades later, is a nuisance to the

process of digital conversion. Each metal fastener, sometimes perhaps rusted

slightly with age, is a mortal threat to the integrity of the paper into which

it was long ago set in a brief but violent act of practical necessity. And the

staple considerably slows the process down. A few short months expands to,

perhaps, years of careful, tedious effort. Karin and her team managed to

do a few dozen boxes before it was negotiated that the whole lot would be

packed in Boston into a large U-Haul, whereupon through the ice and cold of New

England it would be driven to the balmy hot environs of the Gulf of Mexico, to

Houston Texas, unloaded and delivered to the careful curatorship of Rice

University’s Woodson Research Center.

From Karin’s beautiful essay on the joys of digitization,

we’re delivered to the staid eloquence of the Center’s master director, Amanda

Focke, joined by Anna L. Shparberg, the earnest-seeming and very devoted

Humanities Librarian at Rice. It is under their care that the extensive Mack

Archives will remain for the next few years as this digitization project

(Digital Humanities, anyone?) is brought to completion. So, it seems that there

will be some time before the general scholarly community will have access to

these rich and likely rewarding archives (which, Greg Eghigian tells me, he’ll

be making use of as he turns his attention towards the whole contactee

phenomenon that has paralleled the UFO story).

With this I will delay to a separate, final post what of the

last day of Archives II I was able to attend and therefore review. I do

this also because I have no doubt tired the reader beyond what is reasonable

(if to tire the reader is reasonable), possibly myself having gotten

lost in a thick field, laden with weeds, of the possible and the impossible,

the dense forest of ideas, facts, of minds and bodies. Let us therefore rest

for a moment, and take up these reflections again soon.

Thank you for this excellent overview of this portion of Archives II, Mike! Wish I could have been there in person with you.

ReplyDelete