Of workshops and colloquia: a foray into ufological circles and discussions

Before I get to the past, let’s deal with the future.

While attempting to fulfil my duties as president and acting

director of the Society for UAP Studies, and lecturer in philosophy, I

have been trying to work out some of my ideas on matters related to the study

of UAP—which of course inevitably brings

one to the doorstep, if not the very interior of, the “ETH”. And with that one

must inevitably wonder about the nature of the “ET” in the H. But—as you have

come to expect, perhaps, from me as a philosophically-inclined writer on

ufological matters—one must wonder even more fundamentally, as my friend Bryan

Sentes has often stressed, about the very concept of “intelligence” and what is

presupposed by it. Having been positively (and sometimes negatively—but in a

good way!) influenced by Bryan’s subtle questioning and interrogation of the

issue, I am increasingly more inclined to think that while it might be somewhat

obvious (for some cases, both historical and future) that there is an

intelligence behind some (and by no means all) UAP, because of the radical

empirical distance between human and nonhuman, non-terrestrial being,

coming to know what that intelligence is, and the extent to which the

notion of ‘technology’ is suitable for such being, is going to be a much harder

question to resolve. And I think it will be complicated by the fact that, most

likely, there will be a great range of kinds of intelligence in play, each

perhaps with a characteristic relationship to the tools they fashion and use.

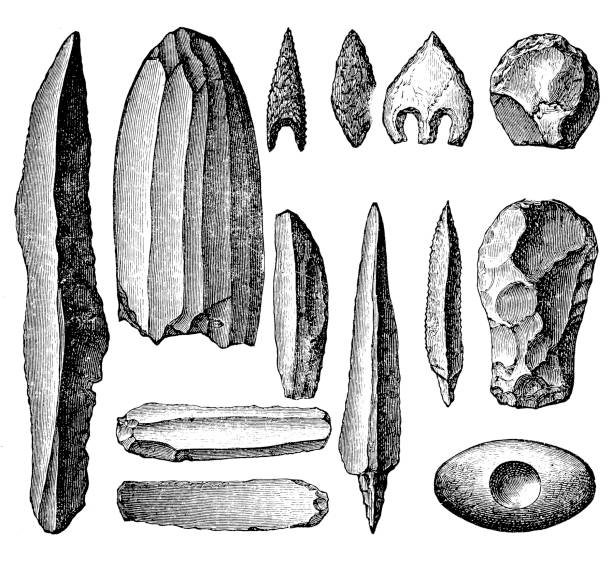

Some perhaps will seek to ambiguate the dichotomy—pronounced for homo faber—between

creator-user and tool used. What SETI expects, for example, is to detect

technologically-induced atmospheric peculiarities in the distant worlds whose

spectra we are just now being able to study in detail (thanks of course to new

and more powerful observation technologies); and with even more powerful

technologies of observation, to perhaps see the megastructures and other

shiny add-ons that a technology-using extraterrestrial civilization would

construct atop their world. But as water worlds might be more common, this

could be complicated by beings who prefer an oceanic and submarine lifestyle.

But the presupposition here is that there will be differences in these

distant world’s observable, physical characteristics that will point to

technology and hence to the operation of some extraterrestrial intelligence.

Indeed, the historical irony here is that science has fallen back on the

favorite “proof” of theologically-inclined intellectuals (and “natural

philosophers”) of the 17th and 18th centuries: the

“Design Argument”. William Paley, of course, gives us its classical form (which

we quote at length):

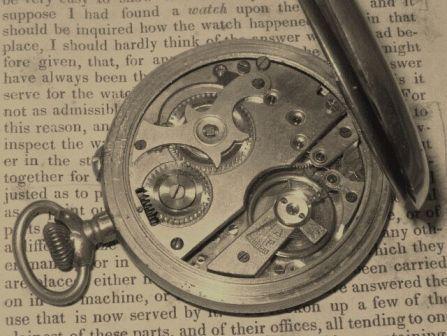

In crossing a heath, suppose I

pitched my foot against a stone, and were asked how the stone came to be there;

I might possibly answer, that, for anything I knew to the contrary, it had lain

there forever: nor would it perhaps be very easy to show the absurdity of this

answer. But suppose I had found a watch upon the ground, and it should be

inquired how the watch happened to be in that place; I should hardly think of

the answer I had before given, that for anything I knew, the watch might have

always been there. ... There must have existed, at some time, and at some

place or other, an artificer or artificers, who formed [the watch] for the

purpose which we find it actually to answer; who comprehended its construction,

and designed its use. ... Every indication of contrivance, every

manifestation of design, which existed in the watch, exists in the works of

nature; with the difference, on the side of nature, of being greater or more,

and that in a degree which exceeds all computation.

From which we are supposed to derive the conclusion that

there must be a grand Designer, God…

SETI, of course, seeks to establish not that there is God, but

that, if we happen upon the equivalent of a watch on some distant world, then

“there must have existed, at some time, and at some place or other, an

artificer or artificers, who formed” it “for the purpose which we find it

actually to answer; who comprehended its construction, and designed its use”.

The presupposition here being that its “contrivance” and “design” is

manifest—that is, plainly and unambiguously given. Surely this is only

the case because our recognition—in Paley’s famous little thought-experiment—is

given by an object of our own familiar design. And equally as surely for Paley, Nature

Herself manifestly exhibits a design which requires there be a Designer. The

modern scientific rejoinder to this logic is a double critique: (i) the

attribution is an anthropomorphic projection and illicit generalization to all

of nature (no caps), who operates (ii) by blind (unintelligent) chance (with a

logic all of its own: the logic of random but constrained and therefore

knowable circumstance: enter evolutionary biology—the Darwinian reply).

Yet, if we focus just on the artifice of the object itself, we might convert

this theological argument into an argument for the (inferential) existence of

ETI on a distant world, thus resurrecting the theological argument and

repurposing it for SETI. But what about the argument that Paley was

anthropomorphizing: projecting a human concept of design onto nature? Well, but

if we don’t attempt the projection onto nature as a whole, and hence use the

concept of design, patterned after something clearly human in origin, illicitly

in that way, then we can (surely?) use it as the basis for recognizing the

designs of another designer like ourselves, right? Well, that would seem

right—except that we’d have to be able to recognize those designs as designs—an

“artifice” distinct from the general pattern of the “natural world” which would

not to us indicate the existence of an intelligence. So, are the necessarily

anthropomorphic concepts of design, artifice etc. harmless in this case? We are

back to the N = 1 problem: we only have one example of “technology” and

(supposedly) nonnatural “artifice” to go on, and that’s the shiny, polluting,

invasive and adjunct apparatus of modern technoscience, which inserts itself

all over the globe in ways that, for us, seem both obvious and (to some)

unfortunate. Yet to a distant observer, perceiving us with a radically distinct

set of presuppositions (that perhaps do not entail a radical distinctness

between tool and user/being, or between being intelligent and being

natural—i.e., a “nature” of nonseparable wholes and parts), it might be that we

are seen, together with our tools, as part of one whole system of (natural)

being. And if those distant, extraterrestrial observers (and maybe they have

stopped by already?) cannot (or will not) separate us from nature as we

separate ourselves from it, then wouldn’t we expect silence from them,

overlooking us for a larger view of the whole? (Notice, this is not the “ant”

hypothesis many like to toy with when it comes to thinking about the possible

nature of an ETI; rather, I am saying that it might just be incompatible

conceptual presuppositions—which has nothing at all to do with a supposed

difference in intelligence—that inhibits contact or communication. They needn’t be “hyper-advanced” for there to

be a communicative mismatch … yet another dubious anthropomorphism I suppose: “advanced” by what measure?)

This gives you some sense of the kind of questions and

problems to which I’ve turned my mind in recent months. I only go on at length

about this because I have submitted (with Bryan) two abstracts to two run-of-the-mill

academic conferences which propose to broach the subject of UAP in relation to

the ETI hypothesis—but in an effort to problematize any future “contact”

scenario. Or at least to interrogate it in a more fundamental philosophical

register. But not only ETI. I have proposed that even the UAP itself, as it

inhabits what I’ve called a “liminal” space (intersecting the known while at

the same time exiting it), presents a more subtle challenge as they, by

their own appearances (and there are important differences among the various

UAP encounters that are rather pertinent here), problematize our conceptual

space of recognition. We see them—but how? We attempt to conceptualize

them—but how? Their empirical distance from us (in more ways than one) suggests

a more fundamental problem: one of quite radical difference, something

that is even anterior to “otherness” or “alterity” (to use the philosophical

lingo). It’s a kind of difference that occasions (I want to argue) a new space

of conceptual possibilities, something outside the coordinates of “natural” v.

“artificial” and so on. Or in any case the UAP are an occasion (at least for

some encounters) for a significant alteration and change in our concepts. But

we have to think ourselves into this new space, thinking with

these phenomena as they challenge those concepts we have ready-at-hand for them.

There is a third conference to which I’ve sent an abstract,

but this one is a conference on (basically) foundational issues in the theory

of probability and probabilistic inference, and I am second or third author

(with some others in the UAP Studies community). And here we are attempting to

interrogate the problem (in Bayesian inference theory) of prior probabilities,

which seems to always militate against truly “new empirical observations” that compel

progress in science: if every potential anomaly is always given a very low

probability against the more likely conventional explanations of it, then

science cannot change—it cannot find a new paradigm formed around and suited

to the specifics of the anomaly itself. Rather, it will always seek to

extend the dominant paradigm (by introducing any number of paradigm-saving

hypotheses). Yet, we know that science has changed; indeed, we accept that

change is part of the very essence of science as such (as a method of discovering

the structure of nature, the dazzle of the real). So, we might ask (following

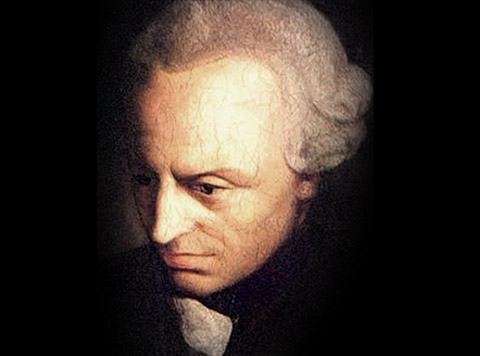

the so-called “transcendental” method of Kant—whom I have yet to introduce to this

project!): how is scientific change possible, since we know that it does

change? That is: what are the conditions of the possibility of scientific

theory change—even radical theory change (as in the transition from Aristotle

to Galileo-Kepler-Newton)? It has to rest with the acceptance of scientific

anomalies, or at least with the embrace of the (un-theorized) new. But how does this happen? Since it cannot be an exactly rational

procedure internal to a given paradigm, then change must be extrinsic to a

paradigm, and must derive from the inner structure of the phenomena themselves,

which compel the creative postulation of new theory. That is, the anomaly

represents a potentially new framework with respect to which there will

be new meaning to certain key concepts. Thus, the assignment of the

prior probabilities must be contextualized or relativized: either

the prior probability of an extraordinary hypothesis (that there is a genuine

anomaly not strictly explicable by means of existing science) is determined relative

to the existing paradigm—in which case the probability will be very low—or

it is given relative to a new paradigm, which would be the one implied

by the anomaly itself. In this case, we would have to examine the priors relative

to a context of anomalies: if the existing paradigm suffers from several or

many, then this would raise the likelihood that we, indeed, have a genuine

anomaly and have reason to believe that the extraordinary hypothesis is more

likely than not (especially if the anomaly can be linked to other anomalies in

some systematic fashion). At least this is my (so-far only partially-baked)

contribution to the paper. We’ll see…

I will also be traveling, on the 9th of May, to the second iteration of the Archives of the Impossible, which is Prof. Jeffrey Kripal’s initiative at Rice University to collect, house and make available a whole range of documents and other sundry resources related to—and what should the term here be?—the uncanny, the strange … that which doesn’t easily fit in with the conventional. Here I will meet the more “woo” crowd (though I hate that term). For my own part (and not to predetermine myself as dogmatic) I represent something of an alternative view of the alternatives. As I’ve attempted to outline in my blog posts over the course of the previous year (and it’s official: though I have slowed my writing these past several months, Entaus is one year old), I am trying to work out a kind of empiricism of the unconventional.

Yesterday in the shower (where lots of ideas seem to percolate from the depths of my unconscious—water is truly rejuvenating to the soul), I had an insight into what it seems that I am trying to say. Let me try to recover this flash of a thought: In the 17th century, Science came to embrace two traditions—the one speculative and conceptual, disciplined by mathematics and elaborated as metaphysics; the other experimental, almost alchemical in a new sense but disciplined by the mathematical and the metaphysical. This produced something remarkable: as the great philosophical writer on the New Science Sir Francis Bacon would conceptualize it, through the synthesis of these traditions, human beings were given a new power of creation. Heretofore hidden potencies of Nature were expressed and brought to light, removed from the darkness of natural secrecy, and opened to the power of human understanding, control and intervention. The metaphysical and mathematical descriptions of Nature, passed through the alchemy of experimentation, produced new forms under the direct control of the human experimenter. Newton (secret alchemist by night) would then show that we could discharge the metaphysical specifics (those “substances” or “essences” of the old medieval Schools) yet retain the structure of relationships that reliably and consistently produced certain observable results or predictions, which could then form the basis of our understanding of Nature: we might not know what gravity itself, metaphysically speaking, is (Descartes had proposed that it was really a plenum of material “vortices” and so really was a matter of frictional forces pulling on things), but its formal, mathematical structure could be given (as a certain characteristic equation, that expressed the right structural relationships between the relevant phenomena). Fast-forward to the breakthroughs of the late 19th and early 20th centuries: we could now not only reproduce and control phenomena heretofore totally unknown to human beings (the phenomena of radiation and radioactive decay surely were all around us, but imperceptible and uncontrollable), but could bring into being phenomena possible but not so far expressed by nature herself. For example, fission, and of course the atomic bomb, wasn’t a process or technique nature seemed to care to express on her own (aside from the randomness of radioactivity); yet, human beings managed to express it for her (for better or for worse). Fusion, the basic process behind the sun, was the very origin of our own life here on Earth (and the process behind the creation of the atomic elements on which that life relies), is already expressed everywhere in the universe, and is a process we are on the verge of mastering for ourselves: Imitatio Dei. Various quantum processes are underway everywhere—but quantum entanglement is much rarer in nature; yet, we can bring this into being (difficult though it is) and make nature express it. What other processes, like fission, still yet remain entirely hidden within the bosom of nature but which, unlocked by the key of insight, will be made manifest—perhaps for the first time in the history of the universe? Surely the entire range of what we now call “paranormal” might be said to be a kind of hint, a dim suggestion of what is possible on the basis of principles of nature yet unknown to us?

How much of our knowledge is simply a function of our perhaps rather peculiar portion of the universe to which we have, for contingent reasons, a certain kind of access? We’ve been thrown into the world at a certain time and place, and though through our vision and our extended perception (by means of more exotic electromagnetic and gravitational interactions) we see everywhere the things we see here in our immediate experience, how much of what we experience isn’t representative of this vast expanse of the Real? The New Science, if it taught us anything, taught us the humility of patient empirical engagement with nature, which by a painstaking process of experimentation and theorization, slowly but surely reveals what is hidden. Nature is the ultimate horizon outside of which there is nothing. Everything is within nature. Paranormal or not. We have only to go deeper to get the unexpressed (or partially expressed) to be more fully expressed. In this way does the human—or any other being of this kind of transformational intelligence—become a constitutive element of the very being of nature herself: a productive and creative element of the very unfolding of the real of nature. We are an expressive function of nature even as we make nature express what is hidden within her. I don’t know if this is why Kripal calls the human “two”, but surely we must have patience—the patience of the empirical.OK, well, that was much more of an elaboration of the insight

I had than I had intended—and one perhaps diluted because of the prolixity of

its expression. It will have to be tightened and pared down for it to be as succinct

as the original flash had seemed to me. But this is my best first attempt. Let it

stand.

So much for the future. But what about the (immediate) past?

Let’s talk about those three ufologically oriented events I had the pleasure to

attend…

During the week of March 13th, I attended a

workshop organized by Alex Wendt and hosted by the Mershon Center at Ohio State

University. The title of this event was given as “Bringing SETI Home: National

Security and the Politics of UAP”. The idea was to bring in a number of

scholars from a range of disciplines to discuss various national security and

political issues raised by UAP—if we take UAP “seriously” (that is, as

more than misperception, hoax, or instrument error). I’m not quite at liberty

to disclose who exactly was present, since the taboo against the subject is

still strong and a number of the scholars gathered at the event don’t want their

careers jeopardized, but there were many present who are quite serious and well-respected

within their respective disciplines. Indeed, I was impressed by both the range

and the quality. It was only a two-day event, but it was exciting, dynamic and

very intellectually fruitful. Such a profound spirit of collegiality and

helpfulness dominated throughout its two days that it could be said that this

event was unique—even among more mainstream academic workshops (at least that I have

attended over the years). We were gathered in a spirit of collaboration and intellectual

exchange while recognizing the difficulties inherent to the topic—which we

always kept foregrounded as we discussed and debated. My sense was that this is

precisely the kind of thing that’s needed in a field that is so young: if these

were exercises in “UAP Studies”—which I’d argue they most certainly were—then we

went some distance in trying to experiment with methods and discourse that

could be foundational to it. It was a rich and deeply meaningful experience, to

say the very least.

For my own part, I presented a talk (based on a very preliminary paper) on UAP and climate change—perhaps a strange pair. But there were papers from those involved with SETI (exploring the problematic relation between UAP and SETI); from those concerned with the politics of any potential “disclosure”; from those concerned with the ethics of a potential military engagement with UAP; and from those concerned with issues of “securitization” of UAP (and this tended to be the general concern of the workshop as a whole). We have planned to develop our papers and talks into chapters for a volume of essays, possibly titled with the title of the workshop itself. There will be three editors of this potential volume, and we’re looking to attract Oxford University Press. We’re hopeful that they’d be interested. If so, then this could very well be a watershed moment for UAP Studies. Our due date for finished papers is fixed for sometime in the middle of January of next year, so it’ll be a while before the thing sees the light of day. But it’s in the works, and should, when finally released, be a rather interesting read…

On March 16th I arrived home. I had flown into Detroit for Columbus, OH from LA, but now found myself returning to LAX (which is essentially a second home for me now) on March 20th, for one of those late-evening departures out to Europe that seem to be rather common. I booked myself onto the big Airbus 380—quite an experience in modern aviation. It’s a wonder the thing can get airborne. But airborne we were, after almost a minute of acceleration down the runway. Off to England I went for event no. 2: a one-day colloquium held in the very old university town of Durham, about a 3.5 hours (very pleasant) train ride up the English countryside from London. This was the brainchild of Prof. Michael Bohlander, the German jurist and international criminal court justice who leads up the Law department at Durham University. The colloquium’s title—“Alien Conversations: An Interdisciplinary Colloquiumon the State of Research and Policy Implications Concerning UAP and other Formsof Alien Encounter”—was a reference to a very famous (some might say infamous) event, held many years ago at MIT, organized by none other than MIT professor David Pritchard (who joined us via Zoom in Durham) along with the esteemed John E. Mack (someone whose esteem might be considered suspect by some). That event was more of a full-blown conference: “Alien Discussions” was the title given, described as a “secret MIT conference” by at least one reviewer in 1993. Mack’s and Pritchard’s event, focused on the abduction phenomenon (wave?) that saw its heyday in the 1990s, yielded a proceedings volume, and examining the table of contents one finds a roster of some of the most famous names in ufology and alien abduction studies—the very state of the art at the time.

Bohlander’s event, no less controversial even if rather less

grand in form and numbers in attendance, found several interesting talks, with mine

being perhaps the least of these, given its informational focus: I was invited

to speak about the journal Limina and the academic society (the Society

for UAP Studies) I founded last year (my talk, which, due to an unfortunate

technical glitch, failed to be recorded, nevertheless seemed to be rather well-received I

have to say). Of especial note was the talk by one of SETI’s more intrepid of

researchers—a leader in the area of post-detection SETI studies. I am speaking

of Prof. John Elliot of St. Andrews (just up the road in Scotland), who, way back

in the late 90’s, pioneered the study of the question of what sort of meaningful

content might be contained in a verifiably anomalous SETI signal indicative

of intelligent life abroad. It’s all well and good to find a signal, and for it

to pass the criteria set to establish it as of non-terrestrial technological

origin; but then what? Might it contain meaningful information? Enter

Prof. Elliot, whose expertise is in the area of computational linguistics (and

he’s quite a brilliant mind, to boot).

The Durham colloquium was simply too short to get the kind of

energetic intellectual exchange going that Alex Wendt managed to achieve at Ohio

State—but then again, it was a really hard sell for Durham to get this

on the docket, and then to have senior SETI personnel to be involved. The

tensions between SETI and the UAP crowd were somewhat in evidence, especially when

one prodded Elliott a bit. But you get a sense that, if we’re looking for

signals afar, and now technological signatures beyond mere electromagnetic blips,

why not “technosignatures” more generally? This is the push given

momentum by Loeb’s Galileo Project, which has no problem with allowing UAP—near

the Earth or on it—to figure into their search. After all, despite the strained

attempts to distance SETI from UAP, there’s absolutely no conceptual reason to

exclude UAP as candidates for an extraterrestrial signature right in our own

backyard—the unconscious fallacy of NIMBY-ism be damned.

Finally, I should at least outline my experiences at my very first

MUFON event as invited speaker. I thought I’d embarrass myself with my talk;

but as it turned out, I don’t think I did too badly. Perhaps I erred in terms of

the content, which might have been a bit too heavy. But I don’t think so: I think

the audience, all 10 attendees in person, and 9 or so online, appreciated what

I was trying to do, which was to find something of a middle-ground between

denialist debunkerism and credulous believerism, to move beyond this dead-end

discourse to something more open but more critical at the same time. Maybe I

wasn’t successful in achieving this; perhaps someone else cleverer than I

can do it right.

My talk was entitled “Transcendental Skepticism” and it’s

based on one of my very first blog posts. Now that I think of it, as I delivered

the talk on a beautiful late April evening in Orange County (it was Wednesday

the 19th), that marked almost the one-year anniversary of my blog.

Interesting coincidence. So I seem to have come full circle…

And so there you have it—my roster of scholarly ufological explorations

for the months of March and April. All in all, a rather rewarding (if tiring) intellectual

experience. I look forward to early May, when I fly down to Houston for the Archives

of the Impossible extravaganza, and later that same month when I embark on

my second ufological European adventure—first to Germany, then to Paris, then

to Portugal. I will attempt to chronicle this sojourn more faithfully in real-time

than I managed for my first set of trips. But as I have too much plated for me

from now and even through until then, and beyond (including preparing for Limina’s

first edition), I cannot exactly promise. I can hope.

Until then, pax vobiscum.

.jpg/1200px-Edvard_Munch_-_The_Sun_(1911).jpg?20150116222524)

Thanks for this. Fascinating reading. Slightly envious that you get to do all this!

ReplyDeleteRe "how can we say that we are living up to our birthright as human beings—as homo sapiens? And how can one profess to love “science” in the widest possible sense of the word?"

ReplyDeleteFirstly, it's not a "birthright" it is an assumption or rather declaration to be homo sapiens, wise man.

Secondly, the declaration of humans being wise is really a lie and fantasy because at the core of homo sapiens is unwisdom (ie, madness) and so the human label of "wise" (ie, sapiens) is a complete collective self-delusion --- study the free scholarly essay “The 2 Married Pink Elephants In The Historical Room" ... https://www.rolf-hefti.com/covid-19-coronavirus.html

Once you understand that humans are "invisibly" insane (pink elephant people, see cited essay) you'll UNDERSTAND (well, perhaps) why they, especially their alleged experts, perpetually come up with myths and lies about everything ... including about themselves (their nature, their intelligence, their origins, etc).