The Eye and the Sky: Machian Themes (Part Two)

Still in the shadow of his teacher Plato, Aristotle defined “metaphysics,” famously, as the study of Being qua Being. Ever since, the meaning of this discipline has confused, and fascinated. If physics was the study of nature (qua nature, we might say—for Aristotle this boiled down to the study of movement or change), then what is meta-physika—the study after or about (or maybe above) that? Well if nature is all (Aristotle in a way brought everything back down to Earth after the transcendent orientation of Plato with his enigmatic ‘forms’ that were supposed to be the existential archetypes of anything, set somehow apart from the world with which we interact while living), then metaphysics is about that ‘all’ as an object of investigation. But how to study this ‘is’ we are part of, that ‘all’ we seek to know in total? One thing has to stand somewhat withdrawn from the totality to be able to encompass it, and the only thing that could accomplish that was thought itself. Thus we have the primitive dichotomy laid down in the very origins of Western philosophy: the divide between thought v. “Being”. For Aristotle this meant an investigation into how nature as a whole (everything or anything that could or will exist) was structured. Aristotle provides a series of “categories” that describe this primitive structure—those things we can predicate to anything that exists. Quality, quantity, substance, etc.: this is the manner in which things “are”. But can such really be disclosed purely by thought thinking Being as a whole? What couldn’t really be grasped it would seem was Being apart from the individual kinds of beings that actually manifest to us. Only those manifest entities disclose anything true about anything that might exist; thus the emphasis fell on the entities and predicating the categories of Being to them—as if it was a structure that was disclosed to us in time (the essential dimension that Aristotle reintroduced to Western thought in this regard). But again, was it possible to know “Being” truly in this manner of withdrawal to the safety, the standpoint of one who witnesses as if from a distance? “Theory” is born in this moment, which connotes this knowing distance. And this reflective procedure would become canonical in philosophy: deducing the truth about things and about nature itself by deducing the true structure of Being as such. What this ended up introducing into philosophy was a confident hypothetical procedure for finding the “first principles” that would dictate the structure of things, and this meant looking for the “essence” on which they depend, the deeper and hidden truth disclosed in time. But what would limit this hypothetical act? Since Aristotle’s system doesn’t allow you to change or alter or intervene in what nature is doing by itself (remember the concept of “theory” requires a kind of withdrawal from things!), thought alone reigns supreme. And so if you think it well enough, then, it has to be true. Well, this didn’t exactly go as well as you might think (!) … enter the Aristotelian system of a science of nature that dominated Western/Middle Eastern thought for about a millennium and a half.

The history of metaphysics is the history of an error—at least that’s how Heidegger understood it. It is the history of the gradual separation of what is at first a unity (the unity of experience, of presence) into a metaphysics of substances in which distinct entities emerge against a metaphysical substratum (a kind of backdrop that guarantees the independence of reality). If we sweep this away, we are left with no metaphysically grounded differences (distinctions given to us as a function of metaphysical bearers of substantial essences, like mind or matter), but rather the surface of differences given to us as irreducible relations between the phenomena that manifest to us in experience. We find ourselves confronted by a radically plural ontological field of “Being”—of what is. Such is the stance of a radical form of empiricism that makes it clear that presence of Being (what we can call a more primal metaphysic) is more fundamental than the metaphysics of substance. In this regard we may distinguish metaphysics (in the substances/entities sense) from ontology as such, which has us starting off in that field of what James would call pure presence, Mach the relations between the manifest phenomena of experience, or Heidegger the lichtung (clearing) against which phenomena are foregrounded.

As I understand it, the crucial move that William James made, after wrangling over his own demon of metaphysical dualism (he had not denied the dualism of mind and matter, but hadn’t rejected it either by the time he sat down to write his monumental The Principles of Psychology in the 1890s) was an entirely epistemological move that was at the same time ontologically rather significant. And this brings us to our own claim at the beginning of this (admittedly heady) post: that all knowledge is really appropriation. But we cannot appropriate unless we, in some sense, come to interact with—or better: participate—that which becomes the object of our knowledge. We cannot maintain the passive stance of withdrawal (of “theory” in the ancient sense). Nothing can really be known except to the extent that it interacts or participates with us. Generally, this occurs as a function of our perception. For James, perception is “knowledge by acquaintance”. I believe this is profoundly significant for our attempt to reconcile the physical and the psychical in ufology…

James’ theory is ultimately supported by his radical empiricism, and only really comprehensible once we give up on the metaphysics of substance in general, and the dualism of mind/matter in particular (or for that matter, on materialism and its various alternatives: idealism, spiritualism and so on). According to James, as John R. Shook in his edited volume of the writings of James explains to us: “when [an] object is perceived there is no relation between two things, because the knower and the known are the same experience. … this kind of knowledge [by acquaintance] does not happen because something in consciousness has correctly represented something that is not in consciousness. Knowledge by acquaintance happens because the thing perceived is a part of the stream of consciousness” itself. (p. 20)

In

other words, the object being perceived and the subject perceiving it are not

external (and therefore transcendent) to each other, such that the one (the

subject) represents the other as something outside of and opposed to it. There

is no such opposition. Rather, they are both internal to each other. The

subject is already internal to the thing (as perceived object), and the thing

is already internal to the subject. In fact, it is slightly more integrated

than even this description would suggest, because the claim James advances is

that both object perceived, and subject perceiving constitute one and

the same undivided phenomenon. Perceiving, which James calls “knowledge by

acquaintance” is not the creation of a mental copy of a thing “outside” of the

“mind” (which defines the contours of the subject in opposition to perceived

objects external to it). Rather, what is being said is quite radical, but

almost common-sensical: the object perceived is already a constitutive part

of the subject, and vice versa: the “subject” is already a constitutive

part of the object known (Hegel would awkwardly try to explain it as that “substance is already subject”). They are, as it were “co-relational”. There is not

one thing distinct from another in this relation; rather, to repeat in other

words, the two form a single undivided relation. And this, for James is

“pure experience”. Knowledge is only possible because of this internal relation

of immanence: whatever I know, I know because I am already a

constitutive part of what it is that is known (and vice versa); my perception of

an object is the object itself as far as I am acquainted with it in

experience. Perception is the activity of the object internal to the

percipient. Perception is ontological: I am a constitutive part of the object,

and it is a constitutive part of me. Again, we have an undivided relation;

together we have a co-relation. Science breaks us out of the passivity of a merely theoretical relation (withdrawn to the safety of mere appearance) to establish for us a functional one: a logic of the specific movement of the thing in relation to it concept(s).

James can argue that there is a “world” apart from “my consciousness” (a sense of an “independent” and “objective” world not a function of consciousness or perception itself) because, Shook continues, he holds that

it is possible for a perceived object to join one or more streams of experience without becoming dependent on any of those streams of experience for its existence. The relations between a perceived object and the rest of a stream of experience are within the stream of experience, so that the relationship itself is experienced. But the relation between a perceived object and a stream of experience is not a necessary relation but instead a contingent relation. The perceived object does not always have to be a part of a stream of experience, but it is possible for it to occasionally join a stream of experience. furthermore, we can only conceive of the perceived object as experienceable, because we do not know how to conceive of the object in any other way. If we remove from our conception of an object all of its features that it has inexperienced, there would be nothing left of the object to think about. Therefore, we must conceive the object as continuing to be a set of related experiences even when it is not part of any other stream of experience. (pp.19-20)

This is not a form of “idealism” (that all that exists is

dependent on my mind or some grand universal Mind, or is constituted by ideas

alone, etc. etc.) because “experience” has no such metaphysical status—rather,

the question is a question of what exists independently … but

independently of what, exactly? If we say “independently of experience”,

well, the answer is simple: apart from the relation internal to experience,

there is nothing we can say about anything—it is a meaningless question.

That there must be something independent of experience (that is not

itself experiential) is to ask for there to be something underlying or

underwriting or guaranteeing a “reality” apart from the experience. But there

is no such thing. “Reality” does not exist. And I really mean

that…

The question itself presupposes exactly the kind of “metaphysical” standpoint

we are rejecting, which James is rejecting with his radical empiricism.

“To be radical,” James was to write in “A World of Pure Experience” (1904),

an empiricism must neither admit into its constructions any element that is not directly experienced, nor exclude from them any element that is directly experienced. For such a philosophy, the relations that connect experiences must themselves be experienced relations, and any kind of relation experienced must be accounted as ‘real’ as anything else in the system. Elements may indeed be redistributed, the original placing of things getting corrected, but a real place must be found for every kind of thing experience, whether term or relation, in the final philosophic arrangement. (ibid., p. 124)

Because we are no longer constrained to introduce an

unjustifiable metaphysical distinction between “mind” and “matter”, and because

of the fundamental place accorded to experience, we are no longer vexed by either

the possibility (or actuality) of paranormality (on the one hand), or its

potential significance in the context of some UFO encounter (on the other).

Indeed, we are now able to take each case in which a UFO encounter comes along

with some instance of paranormality as simply a case in which subject (or

percipient) and ufological object (the UFO, which might itself contain yet

another percipient from its own side)—which are already internally

related to each other according to our radical empiricist positivism—bear some

closer relation that must be examined from the point of view of a potentially new

law relating “mind” and “matter” or “mind” and “mind”. But these terms take on quite

new significance, once we discharge the metaphysical nimbus that attends them…

James was to go on to talk in terms of a “stuff of which everything is composed”—“pure experience”—but this language of compositional determination (the language of making and being produced) is itself misleading, for it seems to require us to think in terms of things somehow being produced or brought into being by the stuff of experience, when in fact all we begin with are the given relations within an experience that is not then related to something else (a third underwriting something outside of the mutual relations). James (understandably perhaps) still feels the force of the substantialist metaphysics we are here abandoning, and which must be abandoned if James’ own philosophy is to be properly appreciated for how radical it was (and still is). If we abandon “mind” as substance, then we also abandon matter as substance as well. That is, we abandon substantialist metaphysics as such. With this goes the language of compositional determination. To repeat: what is left over after this abandonment is nothing but a surface of infinite plurality, of relations given within experience. Objectively described, this is a “world of pure experience” not, crucially, a world that emerges from, or is somehow composed of (or brought into existence by) the “stuff” of “experience”. James, the psychologist, makes the case for ditching “consciousness” as a metaphysically grounded entity or stuff, but seems not to go after matter, the third-person exclusionary ground of objective determination—the equivalent metaphysical ghost haunting the sciences. Mach, the physicist, does. Thus, to complete the radical empiricism of James we require the final gesture accomplished by Mach’s empiricist “positivism”: the ditching and delegitimizing of matter itself. We have here neither a mind-dependent perspective, nor a mind-independent perspective. Rather, we have only the immanent relation between knower and known: neither first- nor second-person. This is something entirely new (and not something necessarily appreciated by James himself. (The result, I am arguing, can best be understood as a form of Spinozism—but that is an issue we can’t specifically elaborate upon here.)

“For twenty years past,” James writes,

I have mistrusted ‘consciousness’ as an entity; for seven or eight years past I have suggested its nonexistence to my students, and tried to give them its pragmatic equivalent in realities of experience. It seems to me that the HR is ripe for it to be openly and universally discarded. … To deny plumply that ‘consciousness’ exists seems so absurd on the face of it—for undeniably thoughts do exist—that I fear some readers will follow me no further period let me then immediately explain that I mean only to deny that the word stands for an entity, but to insist most emphatically that it does stand for a function. There is, I mean, no aboriginal stuff or quality of being, contrasted with that of which material objects are made, out of which our thoughts of them are made; but there is a function an experience, which thoughts perform, and for the performance of which this quality of being is invoked. That function is knowing. ‘Consciousness’ is supposed necessary to explain the fact that things not only are, but get reported, are known. Whoever blots out the notion of consciousness from his list of first principles must still provide in some way for that function’s being carried on. … My thesis is that if we start with the supposition that there is only one primal stuff or material in the world, a stuff of which everything is composed, and if we call that stuff pure experience, then knowing can easily be explained as a particular sort of relation towards one another into which portions of pure experience may enter. The relation itself is a part of pure experience; one of its ‘terms’ becomes the subject or bearer of the knowledge the knower, the other becomes the object known. (“Does ‘Consciousness’ Exist?” in ibid, p. 106)

Mach was to be equally critical of matter (and specifically

of the atomic theory under development during his time), ultimately dismissing

the concept, arguably, as a meaningless vestige of a bankrupt metaphysical obsession of

philosophic thought introduced by Plato (or, if Heidegger is correct, by a certain

persistent misreading of him). What has troubled so

many about Mach’s position (even for Rovelli) is his insistence that we find the root of our concepts

of the “physical” world in experience—or, as Mach himself puts the point: in “sensations”. But having

already undertaken James’ withering critique of the matter/mind split (or, more

generally, the distorting dichotomy of subject/object that gets problematically correlated to the mind/matter duality), we can

better appreciate what Mach was trying to accomplish within the heart of

physics—right within physical science itself.

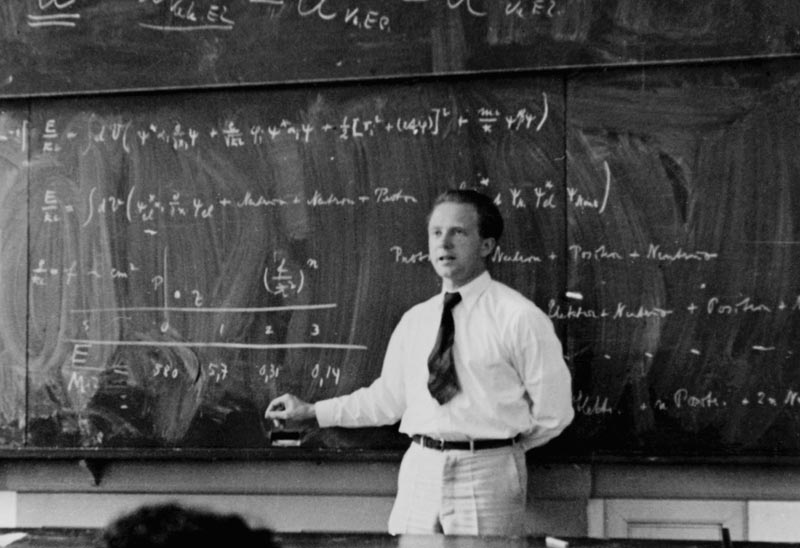

In the next part of this series, we move on to that naivety that perhaps only a brilliant young Heisenberg could be free to explore for fundamental theory, once he had taken to heart the positivism of Mach. This move which Heisenberg makes is the crucial one, the one that indicates for us a potential research program—perhaps the “new paradigm” sought after by so many in ufology (and beyond)—or at least a first shot at a more robust theory that can handle the normal and the potential paranormal without breaking with science as such. Without, that is, drifting too quickly into gnosticism, the “occult”, or the reactionary materialism meant, we can only assume, to restore and defend rationalism (whatever that’s supposed to be).

Comments

Post a Comment