To Go Where No One Has Gone Before: the SCU “Anomalous Aerospace Phenomena” Conference (AAPC) 2022 - Day Two

Day Two was rather more interesting–but of course it was a full day of presentations, panels, and networking sessions. It started off with a bit of a technical problem, since the slides couldn’t get loaded properly, but we were eventually treated to a presentation by the very staid Prof. Hakan Kayal of the University of Würzburg, who discussed mostly his numerous technological projects that are (or will be) put to use for researching UAP, SETI and other space-related matters. This talk was more of a menu-style talk, presenting the various technological options Kayal and his various teams (involving many of his students at various levels) are developing to advance UAP studies, SETI, etc. There were clear synergies with the work that UAPx is doing, and this was eventually explored, with even the suggestion made of reestablishing the kind of collaborative student-exchange that had actually existed between Kevin Knuth’s university–SUNY Albany–and Kayals’. This was a bit of a happy and fortuitous coincidence, and it was a delight to witness the talk of collaboration. One hopes to see this start to happen more and more as academia opens its doors to the UAP enigma. And that was the other topic that Kayal ended up expounding on: that his university is in fact the very first (surely in the EU) to offer a course of study focused on UAP (at least in its scientific/physical aspects–Kayal doesn’t immediately strike one as the kind of a professor sanguine about anything involving “high strangeness”. And we can imagine he jumped off Col. Alexander’s Mystery Train at about slide #600, when we switched from the physical to the psychical (every possible psychical you could think of). But one sensed no hubris in Kayal, no “enthusiasm” (as was the feared label once upon a time, which meant being carried away from your rational wits)–the kind of a person one wants tackling something that can trigger so much bad ju-ju in you, or send you too quickly to the woo-woo camp. Kayal’s work is surely something that serious UAP studies folk must keep on the radar…

Next for Day Two was Prof. Alexander Wendt’s fascinating talk entitled “Dangerous Knowledge: UFO Science and the Last Humans”. Wendt announces that he’s going to dig in and double-down on his earlier thesis, published (along with his mentor Raymond Duvall) over a decade ago in the very mainstream journal Political Theory. It is really a seminal paper, since it actually takes the “extraterrestrial hypothesis” (aka ETH) and the UFO phenomenon seriously. In that paper Wendt and Duvall try to explain the existence of the very puzzling “authoritative taboo” that has existed regarding the investigation of UFOs. The way that investigation is dismissed is telling, they show, because the assumption in dismissing it is that the UFOs can’t be extraterrestrial, so every UFO sighting must have a (literally) mundane (and rather conventional) explanation. The problem is that we don’t actually know that UFOs are not (or cannot be) ETIs (extraterrestrial intelligences)–because they are not being seriously studied! Hence, we have a puzzle. This knot is untied by showing that what’s at stake here is something deeper: a principle of modern sovereignty that is thoroughly anthropocentric, and which, crucially, is foundational to the modern state itself. The ETI possibility clearly threatens this. Indeed, the ETI interpretation of the very real UFO constitutes in this regard an existential threat. Thus, UFOs haven’t been systematically investigated by government or academia simply because “the functional imperatives of anthropocentric sovereignty” can’t tolerate it. Anthropocentric sovereignty says that humans alone are truly sovereign, “solely responsible for deciding their norms and practices” as Duvall and Wendt wrote (under constraints imposed, of course by nature–although it’s worth considering the extent to which the history of science and technology is the history of changing what those limits imposed by nature are). But if UFOs could possibly represent the activity of ETIs, then this sovereignty is negated: there’d be another intelligent “kid on the block” (as Avi Loeb likes to say), which potentially imposes new and fundamental constraints on human activity to which we are powerless to respond, or even to challenge in a meaningful way. Dismissal of the UFO as a serious object of investigation, then, is an institutional requirement acting independently of our actual engagement with the UFO itself. To quote Wendt’s extension of this argument in the talk he gave: it therefore represents “forbidden knowledge” (a theme the philosopher Michael Zimmerman took up for the abduction phenomenon in his seminal paper of 1997). Despite the recent loosening of this taboo, we nonetheless still see a great deal of hostility towards the ETH, or even the existence of ETI itself. It remains a safely abstract implication of the modern astronomical realization of the great plurality of other Earth-like worlds, and certainly still a ridiculous interpretation of “unidentified aerial phenomena”–which can’t be non-terrestrial craft anyway, right? Or so goes the voice of this structural-institutional prohibition once again. The taboo didn’t die, it just got refocused. Formerly, the UFO wasn’t even in a sense “real”: it was just swamp gas, misidentification of known phenomena, “mass hallucination” (a convenient fiction if there ever was one), and so on. Today it is admitted to be real–just not really plausibly extraterrestrial in origin. The hope is still held out for some mundane explanation–except you hear the military now admitting that it cannot rule out a non-terrestrial explanation (remarkable considering how such a statement from the Pentagon was unthinkable just a few years ago). Wendt’s focus, however, isn’t so much on proving that his earlier thesis is right (after all, maybe the taboo collapses altogether–it needn’t be a necessary universal constant of political institutions). Rather, what is interesting is that Wendt is focused on what happens when or if this taboo actually collapses and it is openly admitted that the most likely explanation for the anomalous evidence the government actually has in their possession is that these phenomena represent the activity of some as-yet unknown extraterrestrial intelligence. If the UFO taboo prohibiting serious investigation into the phenomenon was an institutional requirement meant to preserve anthropocentric sovereignty, then it was also protection from the ontological shock of there being a superior technological power rendering all modern nation-states impotent–and thus shaking the very foundations of the social contract ensuring a stable institutional relation between citizen and state. If there are intelligent beings displaying their clearly superior technology openly in our skies and right next to our military materiel, which every modern nation-state is powerless to stop or to challenge, then the state is no longer the guarantor of the safety of its citizens. If the state cannot guarantee this, its most basic function is undermined, and its social contract is thereby nullified. Indeed, the ETI/UFO conjunction suggests that there is another possible social or political organization (a nonhuman one) that is powerful enough to challenge every existing state, showing that the force employed by states is ultimately meaningless in the face of this new reality.

What is curious here, of course, is that Peters takes up the role of negotiator–conciliator?–between two ostensible sciences, rather than between, say, theology and the natural sciences: one having a bone fide status (astrobiology, sometimes called “exobiology”), the other struggling to attain it (ufology). Of course, in this blog as a whole we are arguing extensively for the possibility of thinking of ufology as a science; but we pose this question–what would it mean to think of ufology as a science?–rather than assume any answer to it. (I don’t think one can answer the question without asking the questions I raise—but that’s another point.)

Some reflections at this preliminary level might have helped clarify the problem he proposes to conciliate. The purported problem Peters does attempt to negotiate–that the astrobiologists complain ufologists are pseudoscientific, while the ufologists complain astrobiologists fail in the very first duty of any scientist, which for this case, according to Peters, is “to attend to evidence that Earth is being visited by extraterrestrials”–is already sabotaged from the start by his manner of setting up the “problem”. To say that ufologists complain against astrobiologists for not “attending to the evidence that Earth is being visited by extraterrestrials” is to assume a number of things not all ufologists actually do assume. One is already starting ufology off with a very weak, even shaky, position–one certainly tendentious even for ufologists themselves.

So, at least in terms of Peters’ posted abstract, which states the problem he’s going to address in his talk, things are already a good bit muddled from the get-go. Many careful ufologists point out that we simply don’t know what the UFO/UAP really are, and, given the lack of detailed first-order hard data (let’s not forget that even in the best of cases, the Navy cases, we don’t actually have the hard radar, infrared or visible telemetry itself—we only have what the officers claim was recorded by their instruments), we don’t have a sound enough basis to draw any firm conclusions. We can only really make reasonable guesses. In some cases, there appears to be pretty good evidence that the UFO/UAP are solid objects (of some unknown kind) and that these objects move–as Kevin Knuth so very succinctly and pointedly states it–as spacecraft actually do move. Given the other flight characteristics reportedly observed for some of these objects, it seems reasonable to suppose that at least some UFOs/UAP represent technology of non-human but intelligent origin. Such a view would be consistent with the reported evidence, but the evidence as such neither entails nor requires it. Other ufologists think that the ETH is a bad hypothesis because it is insufficient to explain all of the relevant aspects of the UFO/UAP phenomenon that are frequently reported. Some even think there is nothing extra-terrestrial about UFOs/UAP (witness what we can call the “Masters Thesis”: that UFOs are us, from the future—a thesis I remain utterly dubious about, and which has recently made another appearance in Masters’ latest foray into ufological theory).

But of course, this plays into what Peters claims is bothersome to the astrobiologists: that ufologists tolerate “woo-woo and [engage] in pseudoscience”. It would have been nice to see Peters engage the eight or so decades of literature in the philosophy of science which has tackled in great depth this rather fraught question of what counts as science, what “pseudoscience”. But that’s not what we got. As we close this admittedly cursory review of Peters’ talk, let’s dwell on this issue a bit. Given its pertinence for ufology in general, we’ll likely be returning to it later on in this blog.

The problem–called the problem of “demarcation”–is notoriously impossible to definitively solve. Surely there is a difference between bone fide science and something which really can’t be called a science. But how do you actually draw the distinction–what establishes the demarcation between the two? Some set of criteria–necessary and sufficient conditions perhaps? Family resemblances maybe–but then what characterizes the science family members from those pretenders? It turns out it’s just a bad question, really. And the philosophy of science literature largely agrees that specifying an answer to the demarcation problem remains an open question—one not likely to be resolved anytime soon. There are deep reasons, I believe, for this, and it has to do with the fact that science really cannot be conceived purely in the abstract, or in the absence of an entire cultural (even existential) field of meaning within which science is practiced. What matters is not so much its epistemological foundations, so much as the practical reality that it works in very specific ways, and under very specific conditions. The logic of the specific is key here.Every general criterion that has been put forward to distinguish

science from non-science (or pseudoscience)–and perhaps the one most people

know is that propounded (usually with a tight fist on a table in a smoky room

in the 1950s and ‘60s) by Karl Popper: the criterion of falsifiability–has

been at some point violated by some otherwise bone fide science. (The

reader is directed to read this

article which neatly summarizes the main problem here: that what we really

have is a myth of falsifiability regarding scientific theories; we might

even say that we have a rather unscientific dogma regarding it.)

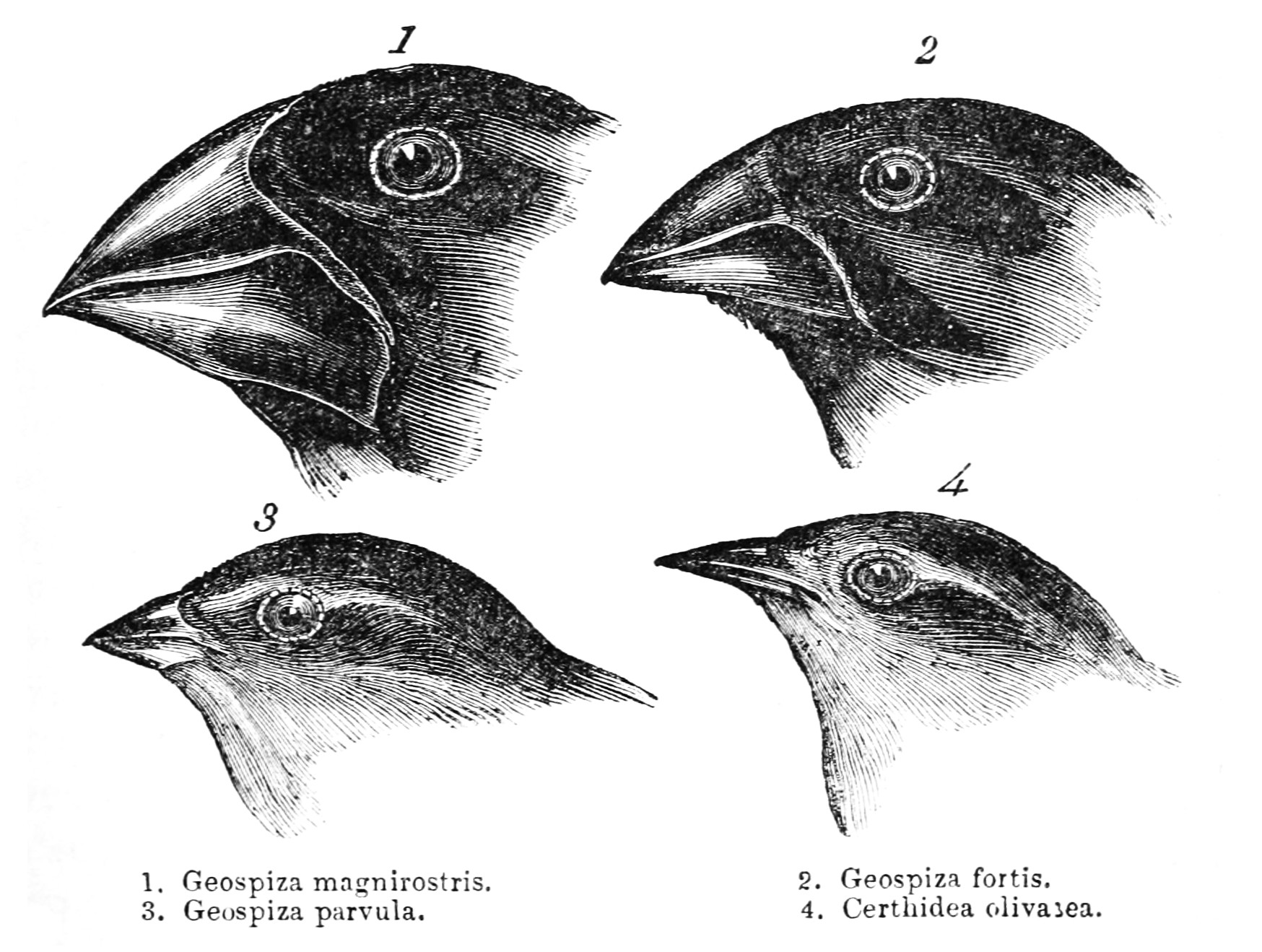

Consider the theory of biological evolution. What would it take

to falsify it? Many have pointed out that evolution as such is not a “theory”

but rather a fact (about fossil records) that itself must be explained. In

other words, “evolution” constitutes an organizing concept for a whole host of observed

facts and existing planetological evidence. This set of evidence is explained

in terms of Darwin’s hypotheses—random mutation and “natural selection”—which yields

certain predictions about the geographical distribution of biological organisms

and how they are related to each other in the present (synchronically) and across time

(diachronically). The resulting theory is powerful in terms of its explanatory

scope, its ability to unify diverse phenomena, and to make certain predictions.

It has in the twentieth century been substantiated by the discovery of the DNA

molecule as the basis for all life on Earth, and the ensuing theory of molecular

genetics which provides a biological mechanism for the phenomena of evolution. But is evolutionary biology strictly falsifiable?

It may be in principle, but surely never in practice:

this is because we only have exactly one “evolutionary” phenomenon, and

that is the evolution of life on only the planet Earth. And we can’t repeat

that. To test the theory as a whole would require finding life elsewhere and

seeing if we find the same biological structure of evolution. Or, we could

imagine establishing the same abiotic chemical conditions present on the Earth in

its earliest days before the emergence of life, and see what happens over very

large time scales (those necessary for us to observe evolutionary dynamics).

Surely this is not possible: not only do we have little understanding of

abiogenesis to begin with (we don’t have a solid understanding of how inorganic

life actually formed into organic and self-replicating life forms—though we

have some guesses), we have no way of actually observing the relevant processes

on the required time scales (say on the order of hundreds of thousands of years).

But thinking a bit deeper about it, this may not even do the

trick, because evolution is itself an organizing concept, something which is fundamental

to observations of the things we call fossils. We see them as evolutionarily

related to each other, and propose how that could be—this then gives us our

evolutionary biological theory. The specific mechanisms we propose for evolution

as a fact about the fossil record may be falsifiable, but not really the

concept itself. It’s a concept that just works: indeed, it seems to be a very

good description of what you see in the fossil record. To say that evolution is

false is to say that the varieties of organic life we observe do not

derive from each other, and that their current forms are not inherently related

to past forms that appear to be similar to present ones (i.e., that the past forms

do not give rise to new and different forms in time, as the past ones die, and

new ones are born). But the point is that the observational evidence does not necessitate

evolution, and is surely consistent with any number of alternative ways of

understanding organic life. So, no amount of observation will refute it. In this

sense evolution is not “falsifiable”. It just makes sense to think of life

evolutionarily, and we can build powerful theories to explain how it works, and

offer supporting theories to give us a mechanism of how evolution acts.

But it’s worse than that, of course. In principle (if not in

practice), no theory can actually be “falsifiable” because every

theory is dependent upon a whole host of assumptions which can always be

arbitrarily adjusted to save any theory. Rather, what ends up happening

in practice, to deliberately save the rationality of science, is that

scientists will simply declare some adjustment to some assumption in a theory you’re

trying to save illegitimate or “unmotivated”, etc. And this happens all the

time. It happened–and even continues to happen–to Einstein’s theory. (His

theory can be rejected in favor of a perfectly Newtonian theory by introducing

the appropriate—Newtonian—assumptions for Maxwell’s theory of electromagnetism

to make the speed of light not a constant but only an apparent constant,

a problem that initially prompted Einstein to develop his theory of relativity.)

Similar observations can be made, mutatis mutandis, for just about every other criterion of demarcation that has been put forward in the attempt to securely demarcate science from “nonscience”—or pseudoscience (I suppose not all nonsciences are pseudoscientific).

The best we can say is that a science is something that works in very specific ways: by predicting what happens in time under certain conditions which are themselves subject to our control or manipulation. From this point of view, our confidence in evolution is bolstered by something over which we can exact a measure of control: genetics. Insofar as all life has some genetic basis, and as we watch the biological development of species of organisms we can study well and note how they adapt and change slowly relative to their environments, our confidence in evolution grows. It seems to be well-supported. It works well to describe and understand what’s happening to organisms as they breed and produce offspring, and so on. So, what counts as a science is going to depend on whether the “theory” works: what the theory’s hypotheses can explain, predict and unify. This much seems certain—but deciding on whether any particular theory (or practice) is pseudoscientific is to say something much more. It is a term of derision, one meant to close down and dismiss. It requires a dogma for the “essence” of “real” science that simply does not exist—and which is itself unscientific. Science, which is to say actual science, is a hodgepodge of mostly unfalsifiable claims and concepts required for its work of organizing data and phenomena, and hypotheses that can be tested against that data and those phenomena. I prefer to think that any systematic arrangement of concepts is a potential “science”. I am very liberal here. Thus, the right thing to say about, for example, astrology, is that as a theory of the goings on of a human life in relation to the movements or positions of heavenly bodies (if that is the right way to characterize it, which is likely contestable) it just doesn’t seem to work. Indeed, if it is to work, then some of its most basic mechanisms (like the structure of influence between a human life and the movements of planetary bodies, stars, etc.) require elements of reality that would seem to radically conflict with what we think we know about how nature works (that, e.g., influences between macroscopic objects are local and causal, and mediated by gravitational and/or electromagnetic energy of a kind insufficient to meaningfully affect human personality). But we might be wrong about this, and astrology—at least to some extent—may very well end up being vindicated. For now, however, it seems implausible—and for very good reason. To honestly adjudge astrology’s viability and “scientificality” we must ask for its central concepts, and examine the extent to which it makes predictions, or seeks to unify diverse phenomena, etc. And again, here astrology seems to falter quite seriously—at least without it being confirmed in those mechanisms or structural relationships that would substantiate it (the brilliant and careful philosopher Stephen Braude, for example, has systematically investigated such possibilities; the reader is directed to read his essential The Gold Leaf Lady for essays along these lines.) But we should not seek to simply rule it out altogether. There may—and I must emphasize may—be a baby we mustn’t throw out with the (plenty of dirty) bathwater.With that, we close our review of the very rich and successful Day Two of the SCU’s brilliant Anomalous Aerospace Phenomena Conference 2022.

Comments

Post a Comment