Interlude No. 1 on reasoning about & from certain UFO evidence

In any science, the most fundamental place from which it begins, is the place of evidence: and this usually takes the form of some observation or experience for which we would like to account. Accounting for what we observe or experience—this does not just happen by itself. This wanting to account for things—this is something that springs from a more fundamental mood, from the interest we take in things. And from our wonder. Why is something the way that it is, and not some other way? How has something come about, as opposed to not having come about at all, or from out of a number of ways that it could have come about—why this particular way it of appearing to us?

Wondering about UAP, we are forced to ponder a number of

questions, which we should seek to clearly distinguish from one another. First,

the objects in UAP encounters are odd, frequently bizarre: what is it we’re

seeing?—this is often the very first question. One of the most elementary, albeit

rather unfortunate, aspects of the UFO phenomenon is that we cannot in any

sustained or consistent way directly interact with the phenomenon such

that we are able to control or intervene in or during the interaction. Surely,

by virtue of the mere fact of its observability or detectability, we are

interacting with the phenomenon. I take this to be an established truth. Because,

however, of this inability to intervene or control or manipulate the phenomenon,

we cannot, as we can, say, in other sciences, develop an exactingly consistent

(ontological) taxonomy, a classification system for the phenomena we describe

nominally as UAP or UFO, and so on. Except purely phenomenologically (observationally)

in terms of how the objects actually do appear to us (and, crucially, under precisely

and exactly what conditions they so appear. Something perhaps not altogether well

investigated by the research community to date would be, in this connection,

the question as to whether there is a pattern to the conditions—and an

understanding of the set of all conditions—under which we observe a

given UAP/UFO). This restriction to pure observation would seem to place the

study of UFOs in the realm of other purely observational sciences, like

astronomy or even cosmology (although we should hasten to point out in passing

that even these science possess some theory which is demonstrable on

experimental grounds, that is, on grounds for which there is the ability of direct

intervention, manipulation and control over key variables. But we should also

note that the key theory in cosmology or astrophysics, general relativity, was confirmed

early on in the famous expedition of Eddington, who observed stellar

displacement during an eclipse precisely in accordance with the exacting geometrical

predictions of Einstein’s theory—that is, it was itself confirmed by a pure

observational determination). This restriction to pure observation complicates

the study of UFOs in many ways (and we will have occasion to reflect more on

this circumstance in future posts).

How is the object constituted—what and how is it made? The

answer to this might provide another insight into the what we

dispatched with a general phenomenological description of its appearance. So

now we worry: two objects might have a similar or even possibly the same phenomenology, but

may in fact be constituted in radically divergent ways. If I look into a lab

and see two beakers of clear liquid, one might nourish, the other debilitate or

kill me. Both are liquid, but of very difference underlying composition. Closer

to our case: I might group together a somewhat strangely luminous flying globe

of light with the structured craft of the classic UFO, or I might lump together

disc or saucer UFOs together with triangular ones, and so on … but are they all

the same for being apparently technological? Indeed, perhaps not even all are technological in a straightforward sense: the globe of light vs. the disc or

(now) “tic-tac” (which is in truth a well-known UFO type in the existing literature

on the subject, such as it is, not something first seen in 2004 off the coast of San Diego, no too far from where I am writing). The technologies underlying each UFO may be

radically distinct, but functionally equivalent (suggesting another

taxonomic-phenomenological curiosity to think about: the structure/function relationship),

further complicating matters. Again, the only way to solve this problem would

be to directly interact with the phenomenon—hold it, touch it, look very

closely at it, enter it or take it apart. Except in extremely rare cases (which

we shall consider later in this blog), we can do none of this.

What about the origin and nature of these anomalous phenomena? Having barely more than phenomenology to work from, we can say little. Following this somewhat protracted interlude we will, of course, engage with Vallée’s hypothesis that attempts to advance our understanding on these two vexatious questions. But from our previous post (“Transcendental Skepticism”) we have been able to conclude one thing about the likely origins for those objects observed, for example, during the events surrounding the “Gimbal” video: aside from the “natural phenomenon” hypothesis, which we considered at some length, we would seem to have fairly good reason to suppose that, not only are the objects caught on video technological in nature (but this is ‘nature’ in name only, for we have no deeper understanding of its specific character), but they are also likely of nonhuman origin. But this origin claim doesn’t go very far, does it, for we cannot say what or who is their originating cause, and wherefrom the makers themselves arise—even from where the craft themselves come. Yet, we are forced, by the vector established by this clear (inductive) line of reasoning from the established evidence we do possess, to so conclude.

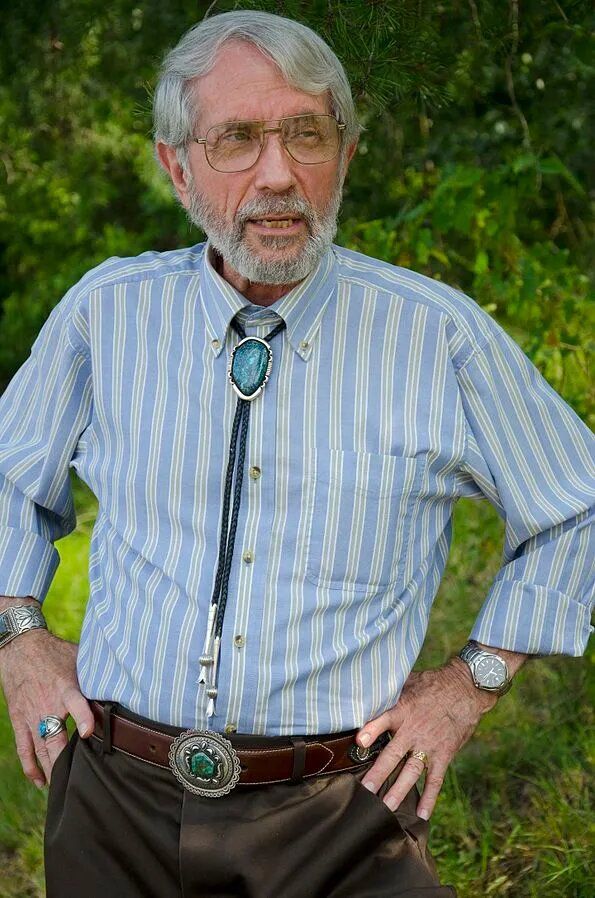

As I lay out this logic, though, I am caused to fall back into myself, and to wonder, once again, but is it all true? Can we be certain of both the provenance and the authenticity of the videos, and the reports of those pilots who claimed to see what we, also, are able to see in their videos. I don’t quite know what would absolutely assuage me of these fears and lingering doubts, except to have had these encounters myself—which I haven’t (although my father had: on one occasion seeing a kind of traveling brilliant luminous globe, in descent apparently, a sighting confirmed in the Philadelphia news the next day, but one whose ultimate nature—anomalous or explainable—was never determined as far as I know.) The resistance to these enigmas is powerful, at least for me. I’m never comfortable with relinquishing doubt entirely, although I can chart the logic of the evidence (and so I am a sealess but map-bound voyager). As with any argument, however, the conclusions one draws are only as strong as the truth of one’s premises. As those premises decrease in likelihood, so does the conclusion evaporate. I have, however, confidence in the veracity of the testimony of Lt. Graves—because not of Graves alone, but because of the preponderance of the evidence given by the overall context within which we must understand Graves’ claims. Without that overall context, and the other witnesses, the videos and then the US military admitting to both their provenance and legitimacy (at least so far as to admit the videos are genuinely military videos of objects they could not identify—with as much credence we place in their own investigative efforts to explain, which might not amount to very much) … without this, Graves’ testimony would be logged as another curious episode in the annals of UFO reports, uncorroborated and therefore evidence from which we should not reason. Let us, however, contrast the Graves report, briefly, with the report (and subsequent claims) of the notorious Ray Stanford, in what we will call the “Stanford Affair”. Since this is a rather fraught subject, I do not want to specifically engage with the very many tortuous details of this case, but rather, as I am wont to do, I will examine in outline the logic of evidential reasoning that pertains to it.

Stanford seems, at least on first blush, to be a rather dubious character. But the question we want to pursue is the difficult possibility that some authentic or veridical evidence comes from bad sources. In other words, the Stanford Affair allows us to determine an important aspect of the logic of examining reported evidence for something (in this case, for a phenomenon which, from other independently verifiable sources of evidence, we might accept as genuine). I want to worry about, that is, the “genetic fallacy”.

What is this?

In the logic of informal reasoning (everyday reasoning), one comes across this kind argument: “well, Jenny is a corrupt official, and she’s lied and even been convicted of perjury before; I think she’s a bit crazy too, so I don’t believe what she’s telling me now—it’s got to be wrong.” Surely, if Jenny walks up to you and says, “you know, the sun rose this morning” you’d believe her, perhaps stopping to wonder why she would make mention of such an obviously true fact? So, clearly and obviously, that the source of information is bad or unreliable, doesn’t mean that some particular bit of information conveyed through that bad channel is wrong—especially if that information is something for which you also have pretty good independent evidence that it’s true. And here’s the rub: we do seem to have pretty damn good evidence for the existence of authentically unidentifiable anomalous aerial (and even sometimes submerged) objects of unknown origin, nature and purpose. Therefore, Stanford’s infamous 1985 video is at least phenomenologically consistent with an established fact—not, mind you, of the existence of extraterrestrials, spaceships, and so on, but of a known or established unknown object of some (provisionally assumed) technological sort. That’s what we appear to see in the stills of Stanford’s alleged video (and we must say ‘alleged’ because, according to at least one analysis, the video itself has never been seen—already a red flag). Reliable sources I am familiar with (if I might be excused to slip into journalistic vernacular for a moment), tell me, however, that, after thinking about the case, their view is that the material is not worth further investigation. (And I am inclined to concur with their opinion.)

Even so, our reflections are useful as an exercise; so, let us proceed. We ask: but what does internal coherence or consistency with other (more well-established) reports really establish? This alone establishes very little, for the argument from consistency may, of course, cut both ways: the video is consistent with other such UFO reports because, well, it is a video of an actual UFO (possibly of the same type as other independently confirmed UFO sightings show); or, the video is consistent with similar sightings because it’s concocted to appear like the ones we already know about. We are, then, right back in the analytical scenario we examined in detail in my “Transcendental Skepticism”. But, let us put forward a somewhat tendentious conjecture—but just for the sake of demonstrating that the possibility that good evidence may derive from bad sources is a live one. The genetic fallacy, in effect, warns us not to immediately dismiss the claims of a bad source just because of the credulity of the source, for truth may nonetheless emerge from the mouths of the dubious.

Given how very deeply convinced Stanford is about the 1985 sighting he allegedly caught on film, we might say that, probably, what happened is that Stanford actually did see something extraordinary with his kids, tried capturing it on film, but got something not terribly interesting or clear (is is rather grainy, as most such photos unfortunately are). For whatever reason (possibly having to do with an effect of the ontological shock of the encounter itself, if not something having a direct connection to the object, as Vallée, somewhat too frustratingly speculatively, wants to argue, as we will see in the following post) Stanford, working from a kernel of truth, proceeds to “fabulate”, that is: to spin the yarn of fiction out of something that, at its core, was an authentically anomalous encounter. Fame, money, etc.—we are all familiar with the usual suspects. Human beings are rather fallible instruments of knowledge and conveyors of information; so, we have to be very careful to separate the source itself from any possible evidentiary content supplied by that source. On closer analysis, of course, it could well turn out that we have an entirely faked video (indeed, on scanning the case, it seems that this is the most plausible scenario), but until this more detailed analysis of the actual video itself is done (rather than an examination of mere stills from it, etc.), we have to remain here cautiously agnostic: maybe there’s something here. We just can’t say with a high degree of certainty (unlike with the Graves and other Navy video cases). The immensely detailed and critical outpourings of an apparently former acquaintance of Stanford’s (Douglas Dean Johnson, a self-described journalist and UFO researcher) would therefore seem to be a bit excessive, as the final determination as to whether the video or Stanford’s claims about it are veridical must await more detailed analysis of the physical video (something which everyone admits we have no access to, if it even exists at all). But…

What is conspicuously absent here, despite claims to the contrary,

are multiple witnesses, and independent, non-first-person corroborative data

that would substantiate Stanford’s claims—something we have for many of the Navy

cases. If we are to trust Johnson’s own multifaceted investigation here, then

we can find neither independent witnesses nor (say) local ATC radar data to substantiate

the claims. Thus, if this is right, we must simply put the whole matter in the

bin of “maybe there’s something here”. It would certainly seem to be a

case from which we should attempt to derive no significant scientific conclusions—apart

from something having to do with the person of Stanford himself … evidence of

some dysregulation? Or just plain greed, vainglory, that is, the usual menu of human

moral failings?

In light of our potentially running afoul of the genetic fallacy,

testimony must be corroborated with as much non-first-person data and extra (independent)

eyewitness testimony to establish a “there” that was there. But testimony might

be fabulist or even false (at least in part) but nonetheless indicative

of a real anomaly, however misleadingly elaborated or articulated it may end up being. The

whole case can be extremely complicated, so without exogenous details establishing

for us the relevant context of evaluation, testimony is just that: he/she said

X. Great! Now what?

Most thinkers of any degree of sobriety allow, that an hypothesis...is not to be received as probably true because it accounts for all the known phenomena, since this is a condition sometimes fulfilled tolerably well by two conflicting hypotheses...while there are probably a thousand more which are equally possible, but which, for want of anything analogous in our experience, our minds are unfitted to conceive. [System of Logic, 1867/1900, p. 328]

What this means for us is that a nonhuman science will most likely have fashioned a radically different theory for the same phenomena with which we interact, for which we in turn have fashioned a divergent account: sciences between different intelligent creatures are most likely radically divergent. But even more vexingly, it might be that the science(s) employed by this different order of intelligence, with which we are interacting in known and unknown ways, possesses a form of being which only partially intersects with ours, as it were, but which, because of their divergent form of being, operates with an entirely unknown (conceptual?) scheme by which they are able to configure nature in what we observe to be various technological ways. That is, the purely conceptual-logical problem of underdetermination is here complicated by a problem of mutually divergent orders of being formulating consequently divergent scientific forms. The classical form of the problem of underdetermination considers different theories formulated by beings within the same order of intelligence, sharing a common form of being; if our technological hypothesis is correct, and with the UFO phenomenon we are dealing with another order of intelligence altogether, then the underdetermination problem is one not just between competing theories of nature, but between divergent orders of intelligence, occupying different orders of being, formulating correspondingly divergent theories. Traditional philosophy of science is alone not enough to deal with this problem. We must understand that we may have here a problem of trans-ontological communication (quite unprecedented in the history of humanity), perhaps even a kind of exo-semiology. We might look at the technology itself that is on display as a kind of sign or indicator of the specific character of divergent orders of intelligence, and the general pattern of suitably aggregated UFO behavior a key to the manner in which those orders of intelligence are interacting with us or, possibly, communicating. (This is in fact something I believe Vallée might be suggesting we ought to consider, as we will in subsequent posts.)

Now we are beginning to drift decisively in the direction of speculation, so it is time to step back, and return to the relative safety of what we do, in fact, think we can say with a measure of confidence: that there exits a core of unimpeachable evidence indicative quite clearly of the presence of something profoundly anomalous in our skies, and that, if the technological thesis is correct, abductions are clearly possible and perhaps likely. (Clearly there are a whole host of rather intriguing issues here that begin to emerge as we afford ourselves the confidence to think the consequences of the anomalous; but such will have to be put off to later posts.)

So, to finish the final point being made: certain abduction specifics are clear, and clearly likely—or at least plausible. Now for the hard question: was anyone actually abducted? I think we can only say with certainty (!) probably so. Thus, we might look for internal consistency to abduction reports: and this folklorist Thomas Bullard, for example, has done, and he finds them curiously very consistent. Therefore, while any particular account of abduction phenomena will likely be dubious, we can reason that the general fact is probable, and that therefore the general structure of abduction interactions (to the extent that they bear internal consistency) is probably accurate. This result is shocking, but I think it follows from this inductively-grounded assessment: people are probably being abducted. (But this claim does not yet proceed to the existential: that there are people who are being abducted—and this is the crucial distinction.)

But who is?

Comments

Post a Comment